MA Project

Project Proposal

The last module of this masters degree course consists of a Final Major Project. This means that we are to come up with a project idea to which we are to explore and work on over the course of this last module that runs for 24 weeks. This first step was to submit a project proposal where we define the research question, the aims, and objectives as well as a preliminary logistics plan explaining how are we going about the project, from research to execution.

Updated Title and Following Up on the Feedback

Following up on the proposal feedback, the new project title is:

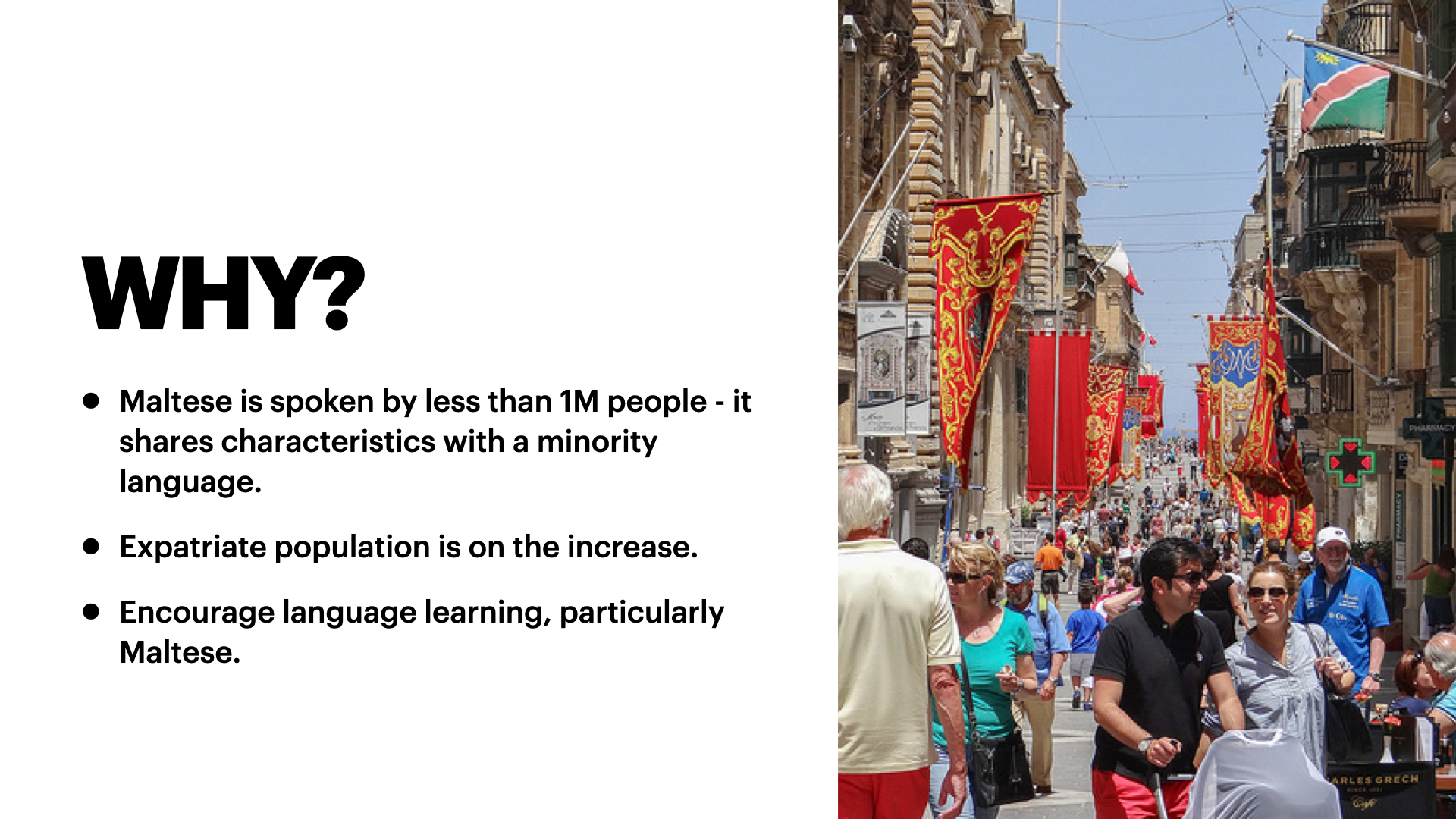

How Can Design Encourage Engagement with the Maltese Language?

Just went through the feedback given on my dissertation proposal. I am very happy with it as it was a positive one as well as constructive – it gave me better insight on which direction should I take for my research.

Starting from the title, my initial intention was to find ways how design can help in promoting the Maltese language as well as culture. As mentioned in the feedback, both are rather broad subject, and thinking back, my original intention was indeed to promote the language rather than the culture. Not that I would omit it completely, as language is an integral part of a people’s culture, however, the main focus would be the language.

When it comes to final deliverable, I am still unsure about what the final outcome will be. In the proposal I did say that it was going to be something ‘to promote’ the language and language learning resources, but I have no set idea as of yet of what I would make. In the feedback, it was said that I should not get stuck on ‘promotional design’, but rather let the research guide you on the ideal deliverable. I agree fully with this, in fact as part of my research, I will be looking at reports as well as statistical data related to language learning as well as migration. In addition to add, I am intending to speak with some linguists to gain better insight on the topic in question. In the feedback, it was suggested also that I look into human the human geography of Malta and look at the history of expatriation in Malta, how settlements differed over the years, whether migration policies changed in terms of the language etc.

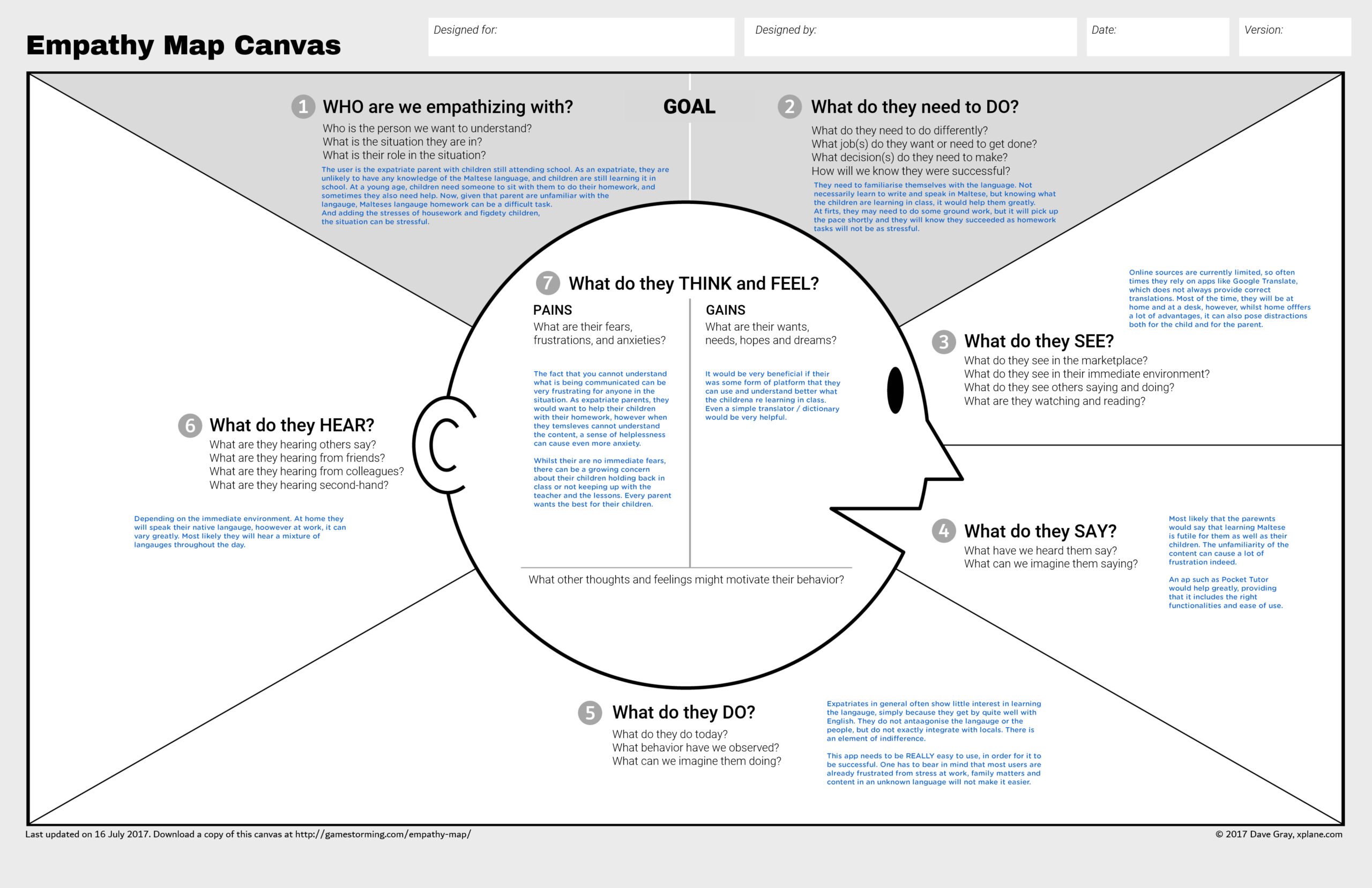

As for target audience, I am still at odds. My main target audience are mostly young (over 18 years of age) and middle-aged expats. However, I do not want to exclude expats with young children. Reason being is because one of the reasons that inspired me to do this project was a German colleague who has a son attending public school and was having a hard time helping him with his homework. Other reasons also include people who had some legal and medical documents acquired from public offices that were only published in Maltese. On this same note, I have started reading a report about language learning and social inclusion, and the focus groups were actually students, and there was a lot of valuable information that will come in handy later on in the project.

Case Study

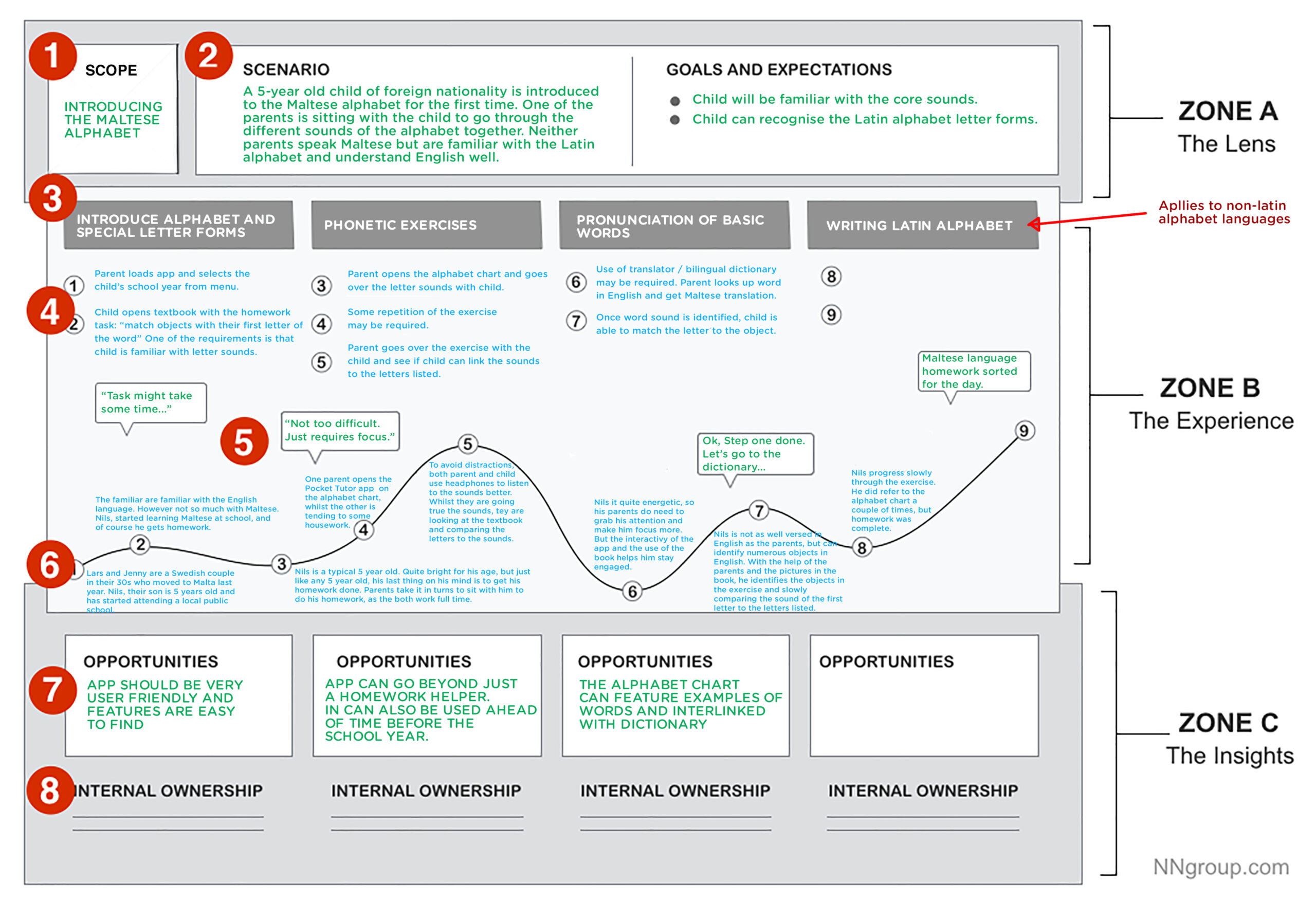

For the second phase of the module, we had to build a case study out of our research question. In my case, I am going to look at how expat parents go about helping their children with their Maltese language homework. As mentioned also in my blog, this was inspired my a conversation I had with an expat colleague who is a mother of a six-year old where we talked about how her son is learning Maltese in school. This case study was to be put together in a presentation and presented to a panel of designers working in different industries outside of the University environment.

Presentation and Feedback

Literature Review

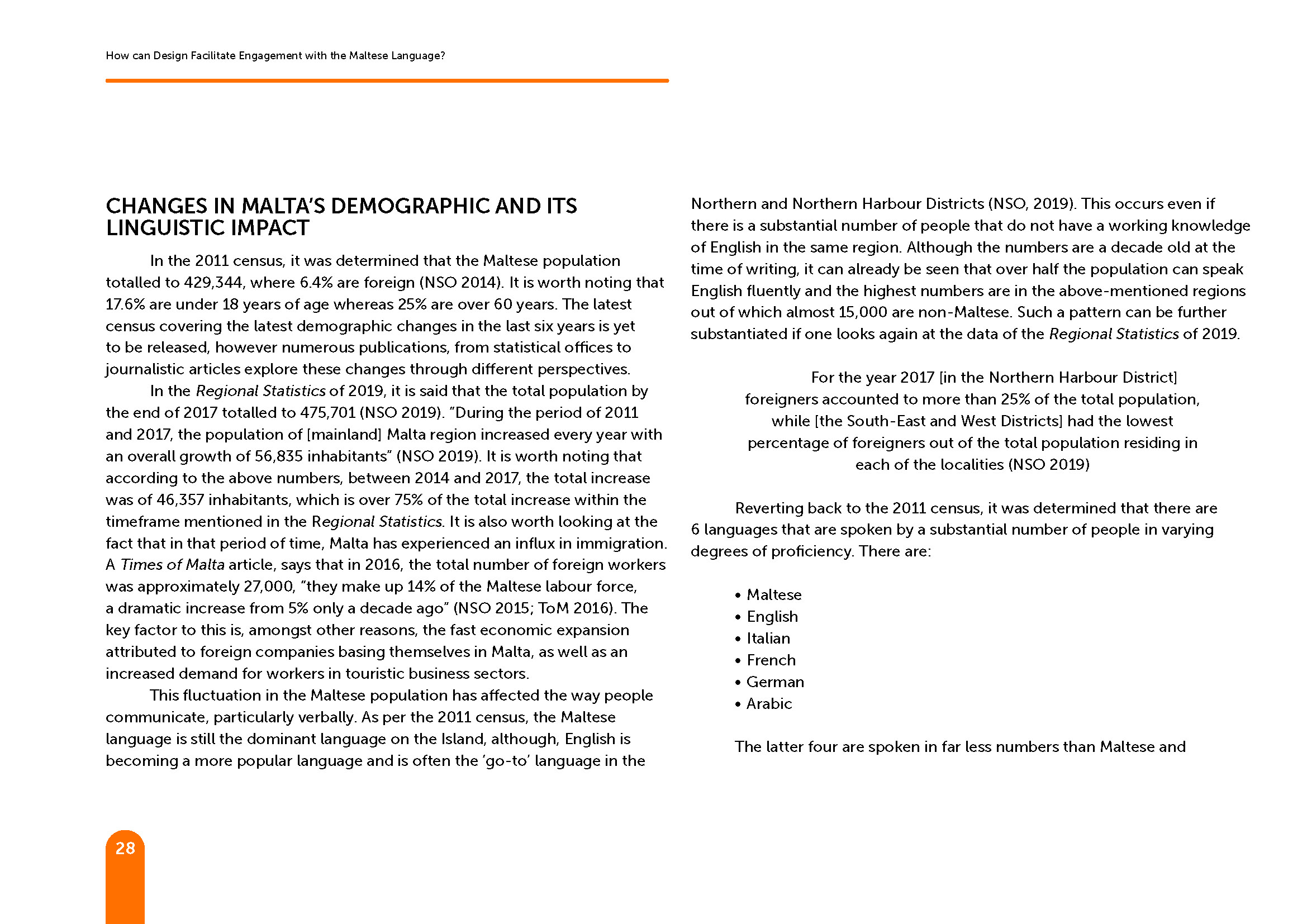

Changes In Malta’s Demographic and its Linguistic Impact

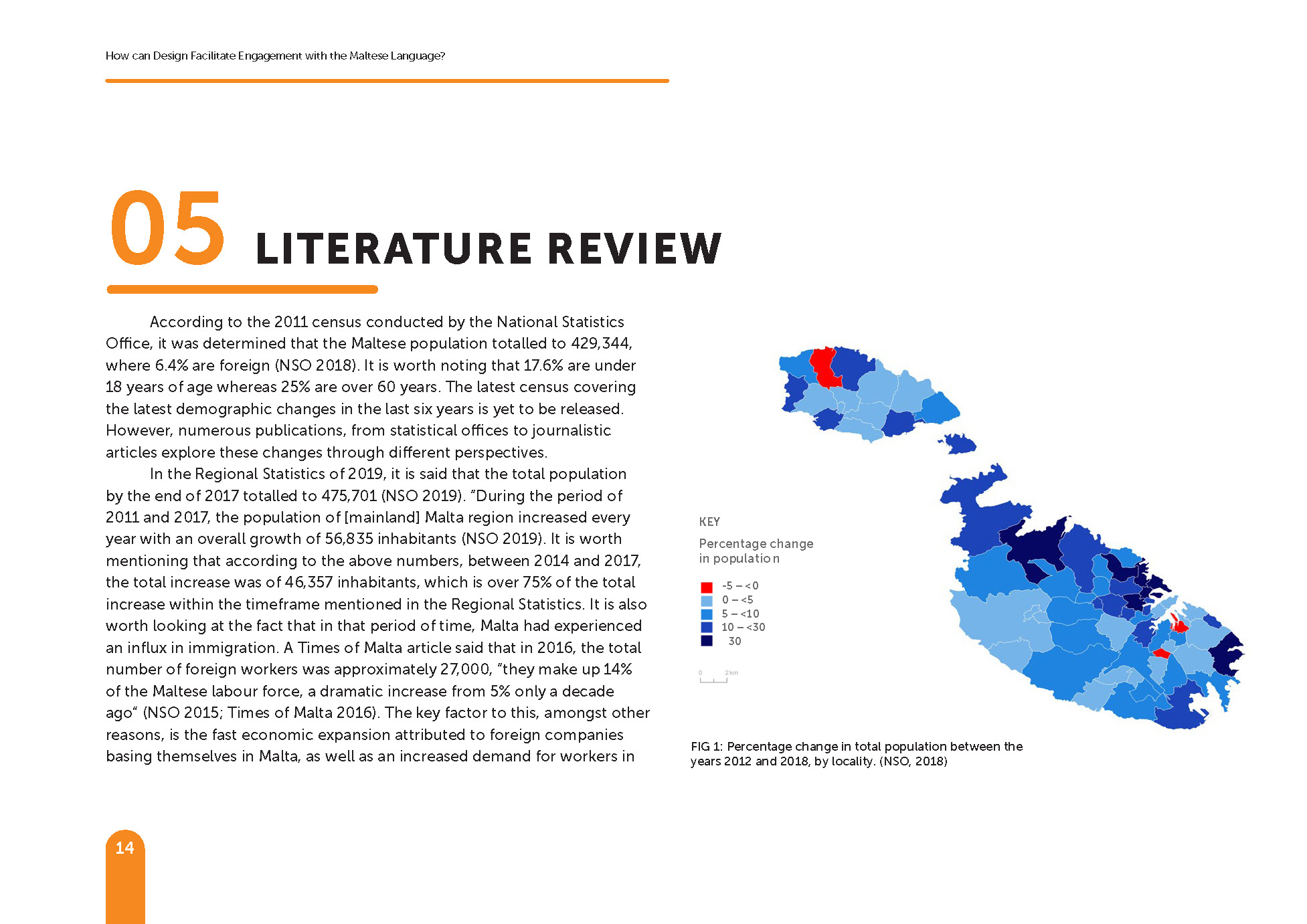

In the 2011 census, it was determined that the Maltese population totalled to 429,344, where 6.4% are foreign (NSO 2014). It is worth noting that 17.6% are under 18 years of age whereas 25% are over 60 years. The latest census covering the latest demographic changes in the last six years is yet to be released, however numerous publications, from statistical offices to journalistic articles explore these changes through different perspectives.

In the Regional Statistics of 2019, it is said that the total population by the end of 2017 totalled to 475,701 (NSO 2019). “During the period of 2011 and 2017, the population of [mainland] Malta region increased every year with an overall growth of 56,835 inhabitants” (NSO 2019). It is worth noting that according to the above numbers, between 2014 and 2017, the total increase was of 46,357 inhabitants, which is over 75% of the total increase within the timeframe mentioned in the Regional Statistics. It is also worth looking at the fact that in that period of time, Malta has experienced an influx in immigration. A Times of Malta article, says that in 2016, the total number of foreign workers was approximately 27,000, “they make up 14% of the Maltese labour force, a dramatic increase from 5% only a decade ago” (NSO 2015; ToM 2016). The key factor to this is, amongst other reasons, the fast economic expansion attributed to foreign companies basing themselves in Malta, as well as an increased demand for workers in touristic business sectors.

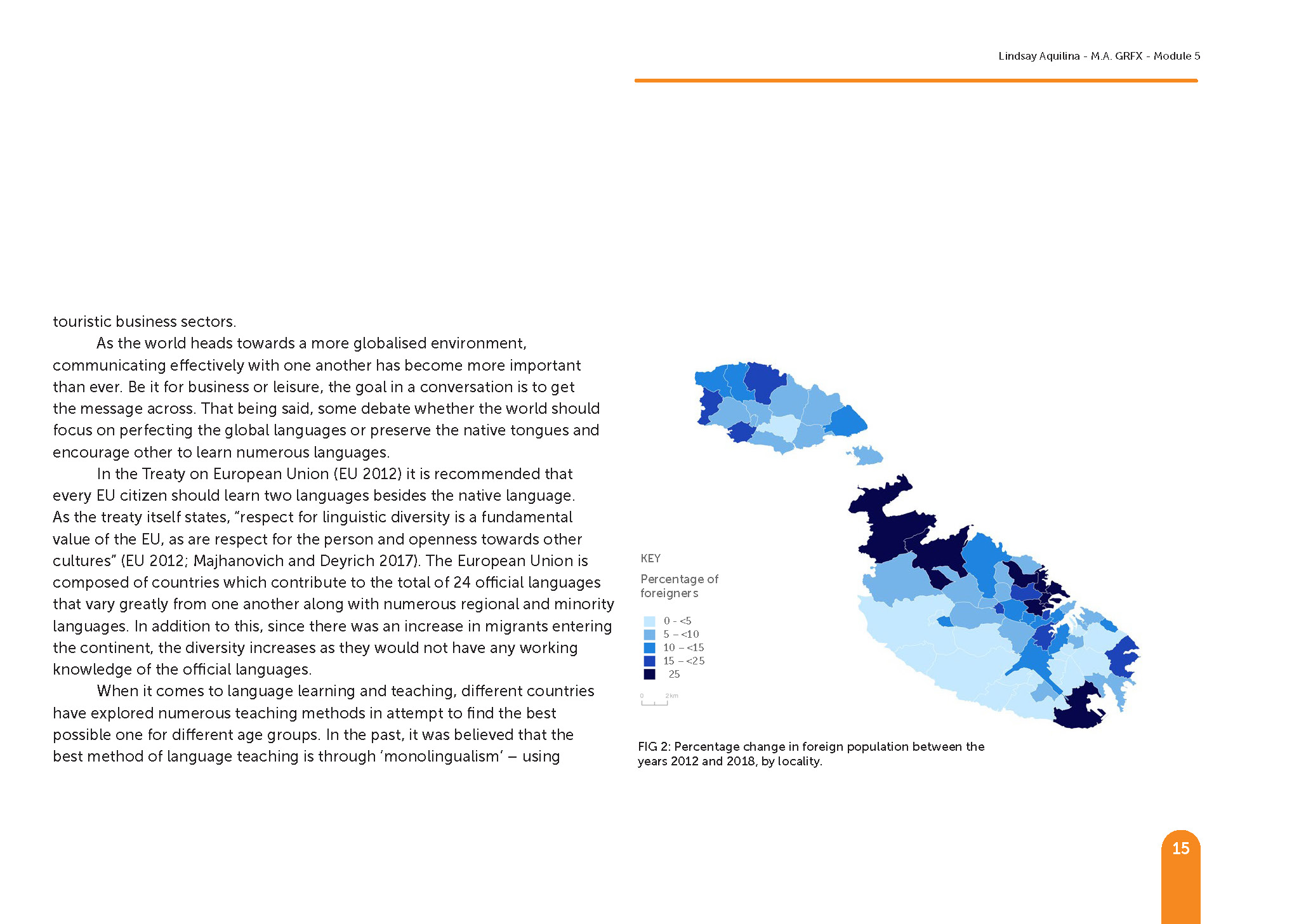

This fluctuation in the Maltese population has affected the way people communicate, particularly verbally. As per the 2011 census, the Maltese language is still the dominant language on the Island, although, English is becoming a more popular language and is often the ‘go-to’ language in the Northern and Northern Harbour Districts (NSO, 2019). This occurs even if there is a substantial number of people that do not have a working knowledge of English in the same region. Although the numbers are a decade old at the time of writing, it can already be seen that over half the population can speak English fluently and the highest numbers are in the above-mentioned regions out of which almost 15,000 are non-Maltese. Such a pattern can be further substantiated if one looks again at the data of the Regional Statistics of 2019.

“For the year 2017 [in the Northern Harbour District foreigners accounted to more than 25% of the total population, while [the South-East and West Districts] had the lowest percentage of foreigners out of the total population residing in each of the localities.”

(NSO 2019)

Reverting back to the 2011 census, it was determined that there are 6 languages that are spoken by a substantial number of people in varying degrees of proficiency. There are:

- Maltese

- English

- Italian

- French

- German

- Arabic

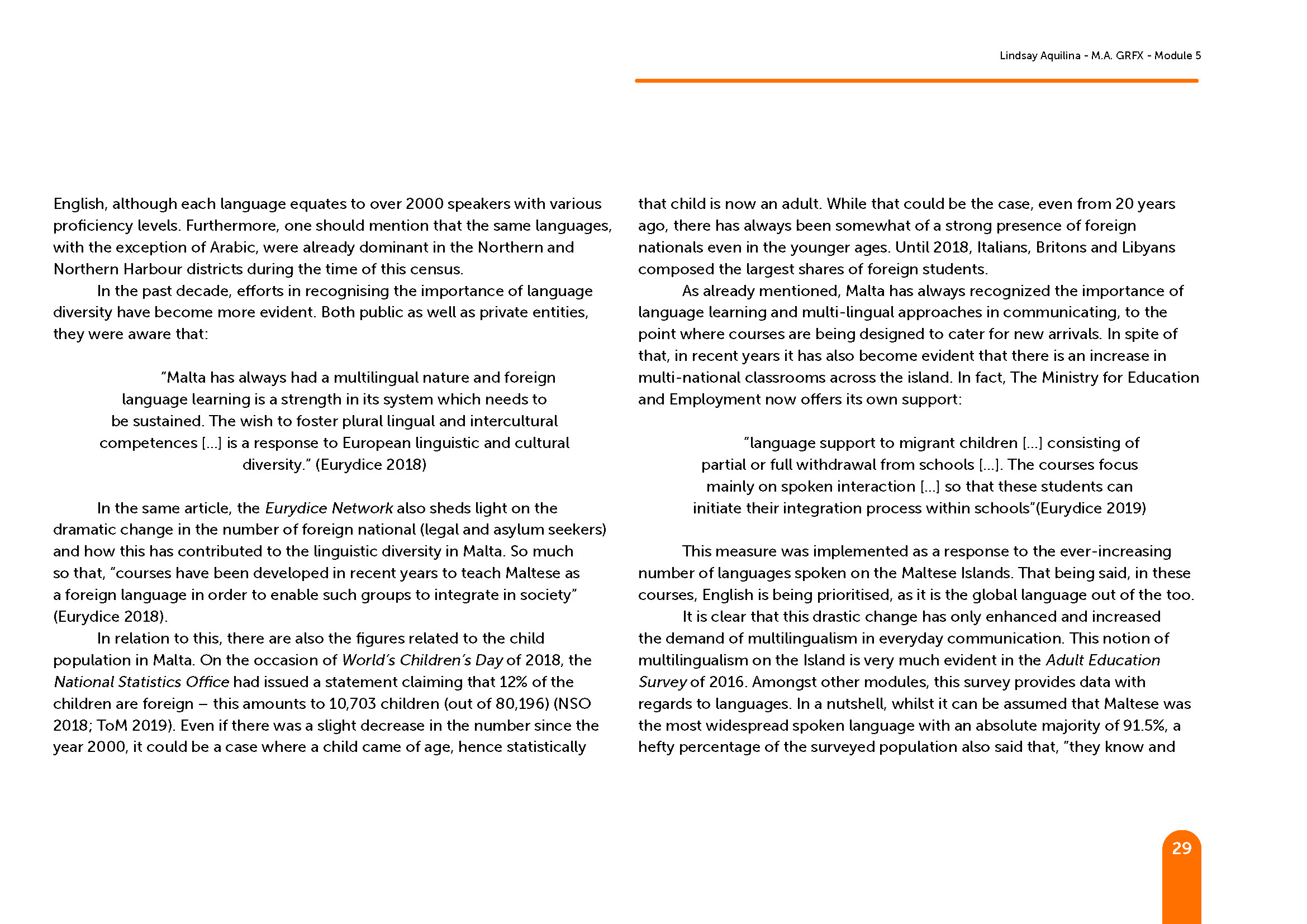

The latter four are spoken in far less numbers than Maltese and English, although each language equates to over 2000 speakers with various proficiency levels. Furthermore, one should mention that the same languages, with the exception of Arabic, were already dominant in the Northern and Northern Harbour districts during the time of this census.

In the past decade, efforts in recognising the importance of language diversity have become more evident . Both public as well as private entities, they were aware that:

“Malta has always had a multilingual nature and foreign language learning is a strength in its system which needs to be sustained. The wish to foster plural lingual and intercultural competences […] is a response to European linguistic and cultural diversity.”

(Eurydice 2018)

In the same article, the Eurydice Network also sheds light on the dramatic change in the number of foreign national (legal and asylum seekers) and how this has contributed to the linguistic diversity in Malta. So much so that, “courses have been developed in recent years to teach Maltese as a foreign language in order to enable such groups to integrate in society” (Eurydice 2018).

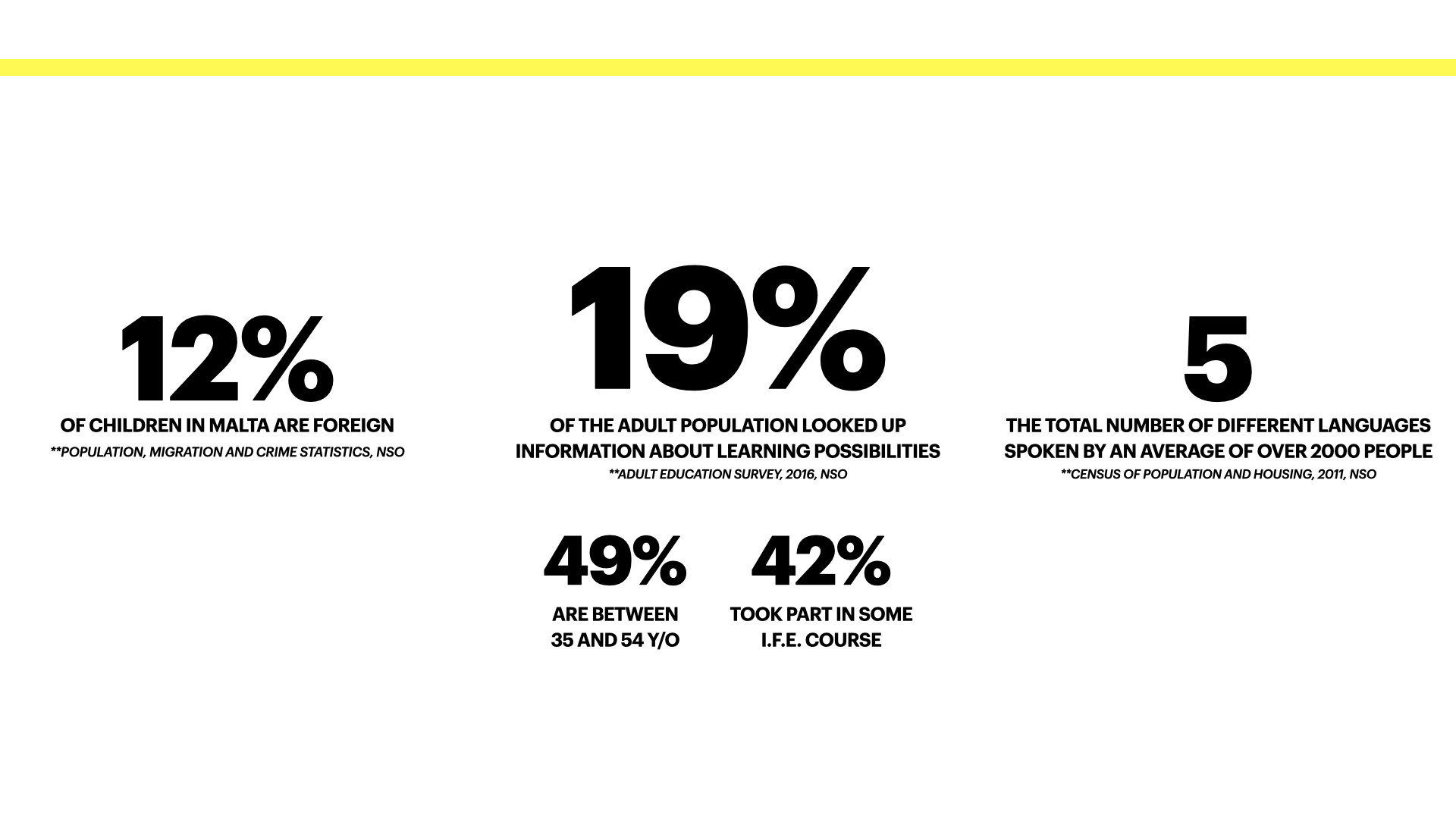

In relation to this, there are also the figures related to the child population in Malta. On the occasion of World’s Children’s Day of 2018, the National Statistics Office had issued a statement claiming that 12% of the children are foreign – this amounts to 10,703 children (out of 80,196) (NSO 2018; ToM 2019). Even if there was a slight decrease in the number since the year 2000, it could be a case where a child came of age, hence statistically that child is now an adult. While that could be the case, even from 20 years ago, there has always been somewhat of a strong presence of foreign nationals even in the younger ages. Until 2018, Italians, Britons and Libyans composed the largest shares of foreign students.

As already mentioned, Malta has always recognized the importance of language learning and multi-lingual approaches in communicating, to the point where courses are being designed to cater for new arrivals. In spite of that, in recent years it has also become evident that there is an increase in multi-national classrooms across the island. In fact, The Ministry for Education and Employment now offers its own support:

“language support to migrant children […] consisting of partial or full withdrawal from schools […]. The courses focus mainly on spoken interaction […] so that these students can initiate their integration process within schools.”

(Eurydice 2019)

This measure was implemented as a response to the ever-increasing number of languages spoken on the Maltese Islands. That being said, in these courses, English is being prioritised, as it is the global language out of the too.

It is clear that this drastic change has only enhanced and increased the demand of multilingualism in everyday communication. This notion of multilingualism on the Island is very much evident in the Adult Education Survey of 2016. Amongst other modules, this survey provides data with regards to languages. In a nutshell, whilst it can be assumed that Maltese was the most widespread spoken language with an absolute majority of 91.5%, a hefty percentage of the surveyed population also said that, “they know and regularly use two other languages” other than their mother tongue, which adds up to 43.2% (AES 2016).

Starting from the younger age groups, taking full advantage of the children’s ability to learn languages, all the way to adults – providing learning resources to help them communicate better with natives – has become important. The authorities, “recognise the importance of linguistic diversity and supports language learning as a lifelong task, essential for economic competitiveness and inclusive societies” (Eurydice 2019). As Malta ranked first amongst all EU countries with regards to population growth “with a net gain of 7,349’ of EU Nationals as well as a “net gain of 9,2019” of non-EU Nationals, it can be definitely said that linguistic diversity is very much present, and recognizing its pros and cons can result in a more seamless means of communication. (EUROSTAT 2018).”

The Diminishing of Languages and Multilingualism in a Globalised World

“Language is a communication tool, enabling humans to convey meaning and emotions, influence other people and stay in tough” (EP 2016). It is a well-known fact that without language, communication is very limited, if not impossible. As it stands, within the European Union alone, there are 24 official languages, along with 60 minority languages along with a number of sign language systems. Europe is a very linguistically diverse continent. 3% of the world’s languages are spoken by 7.1% of the world’s population (EP 2020). With this in mind, the European Parliament as well as global entities such as UNESCO have recognised the imperative importance of keeping this language diversity alive in attempt to preserve lesser-used languages.

It is estimated that “up to half of today’s living languages will be extinct by the end of the 21st century” (Chauvot 2016). In addition, “more than three billion people – nearly half of the world’s current population – speak one of the only 20 languages as their mother tongue” (Chauvot, 2016). In light of this, it brings about the question whether language extinction simply a matter of evolution or is it happening because of (or lack of) human intervention to keep a language alive and update ed to keep up with modern times.

“Languages usually reach the point of crisis after being displaced by a socially, politically and economically dominant one” (Nuwer 2014). This is a statement that has shown up in numerous sources. In a separate European Parliament Briefing – Regional and Minority Languages in the European Union (2016), it states that there is a drastic “language polarity” (UNESCO 2016; EP 2016) and also mentions reasons for languages to diminish similar to the one mentioned above. It adds on to the statement by claiming that “speakers of such languages exposed to such impacts can lose interest or even develop a negative attitude towards [a diminishing language], a stance that is often reinforced by that of the dominant language” (EP 2016).

With this in mind, one cannot ignore the fact that the world is becoming one global village and communication across continent has become commonplace, which means, a certain working knowledge of a global language is required. This brings up yet another question: doesn’t anyone speak English anyway? This is a title for an article publish by Lori. J. Hopkins (2005) for the University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository in the US. Hopkins discusses the concept of multilingualism in the age of globalisation, where she starts off with an event taking place in Wellesly, Massachusetts. Parents had raised money to prevent a second-language immersion program from being removed, as Funds were cut off. In a country like the US, where the mother tongue for many is a global language, a dilemma whether one should learn a second language or not, is very real.

When looking at global language speaking countries, one can see a certain reluctance to learn a second language. In Hopkins’s article, she quotes a parent saying, “kids need foreign language to compete in today’s economy (Boston Globe 2005; Hopkins 2005). However the teacher’s board ruled and rejected the funding as: “the […] immersion program was academic by nature and not an extra-curricular […] program” and therefore, “a second language program […] were to central to the core academic curriculum to be funded by a parents’ group and not by the voting citizens of the community. The immersion program will be cancelled” (Hopkins 2005). So, in such a scenario, who is correct? The parent, or the school board? Hopkins describes the country as “ambivalent to bilingualism”, even though the US is an internationalised country.

Based on Hopkins’s observations and statements, it can be determined that internationalisation and multilingualism can work in synchronisation to bring forward the benefits and best methods of language learning. Yet it is still quite far in many aspects as many immersion programs prioritise global languages as opposed to native languages, including Malta. Many still have yet to understand that even though the world is learning English:

“Monolingualism limit the numerous possibilities offered by a diverse globalised world [and] it also keeps the country from maximising the domestic resources within its own borders, Undoubtedly, the world is acquiring competence in English in order to be able to participate in the areas of commerce, tourism, security and technology [amongst other areas]. But this rudimentary competence, which I […] invariably demand as much from international counterparts […] does not necessarily guarantee meaningful interaction.”

(Hopkins,2005)

A similar opinion is also shared by the European, African and Asian counterparts. The European Union invests large sums of money to conduct studies and strives to preserve languages and promote the concept of multilingualism. Case in point is Malta. Following recommendations from the EU in conjunction with historical reports and curricula, the country has divised a separate language policy aimed for younger children. The Language Policy for the Early Years in Malta and Gozo (2015) specifically “promotes bilingual development in Maltese and English, of young children (0-7 years) in Malta and Gozo. It is intended to provide national guidelines for bilingual education” (MEDE 2016). It is a detailed document, aimed to provide guidelines to educators to create the best teaching methods (which will be discuss later). Malta has recognised the need for language learning as it is common knowledge that the Maltese language is not spoken anywhere.

“The Language practices of individuals, in particular outside school, shape their language use” (Council of Europe 2015). This means that the community in which an individual lives plays an equally important role as what goes on in the classroom when it comes to language learning and the perception towards bilingualism and multilingualism. In a sociolinguistic context, an essential element of a multilingual country, such as Malta, is the ability of its people to switch from one language to another.

Similar perceptions are also present in countries outside of Europe. Multilingualism is very evident in former colonies. This includes countries like Singapore, India and Malaysia. Singapore, for instance, has four official languages. That said, Singapore caters for all of these four langauges even if “hardly any resident can speak all four. English is the main lingua franca used between the different ethnic groups in Singapore” (Lew 2021). Also, English is a compulsory subject in school. However, the “mother tongue” is also taught depending on the ethnic background on the student: Indian Singaporeans lean Tamil, Malays learn Malay and Chinese learn Mandarin. South Africa has eleven official languages. Once again, English is the language of choice between ethnic groups and also that of the government. However, surprisingly it is only spoken by 10% of the total population. In fact, the most widely spoken language is Afrikaans. “Though [South Africans] might not be completely fluent, many people can converse in three or more tongues” (Lew 2021). Through these examples, one can see how a globalised language is integrated in the language system without interfering with the native tongues. It is worth keeping in mind that the above-mentioned countries are very much larger than Malta, hence native languages are spoken by a much larger group of people.

In the Regional and Minority Languages in the European Union Briefing (2016) it is said that there was strife between the regional and minority languages:

“RMLSs [Regional and Minority Languages] are in competition with the dominant languages and under pressure from the population’s assimilation tendency. As long as a language is used by speakers of all ages and in all domains, there is no danger to it.”

(EP, 2016)

The problem arises once people would stop speaking it and/or is not available in certain domains. In this briefing, there is a reference to what the UNESCO deems as threats to diminishing languages were outlined back in 2001, as part of a language vitality action plan These are:

- Domains of use

- Population of speakers

- Their attitudes towards the languages

- Socio economic interest

Following this, UNESCO’s main recommendation was to present the language in question in domains people are making use of the most, in particular the internet and digital media. A separate research project – the Renewal, Innovation and Change: Heritage and European Society (RICHES) also stated that “providing multilingual content and access to cultural heritage websites would facilitate a sense of belonging and of sharing common heritage” (EP 2016) as languages are indeed part of a people’s heritage, hence learning about other cultures can also be done through languages.

It can be said that different continents see multilingualism in very different light. The countries that are reluctant to learn a new language are likely so because they have one official language that also happened to be a global language, whereas more linguistically diverse countries are more receptive. In this case, it could be because knowing multiple languages is a common trait. The correct answer might still need to be determined, if there is one, albeit research does show that language goes beyond day-to-day conversation.

“Over the years, the EU has undertaken education-related initiatives at all levels of teaching, including with regard to research that facilitates the production of RML teaching materials, the presence of RMLs in cyberspace, and the work on modern-world RML terminology. It has also recognised the need for RMLs to be taught to non-native speakers and has supported their media dissemination. The European Parliament has supported the promotion of RMLs and called for the protection of endangered languages.”

(EP 2016)

Benefits of Language Learning

As the world heads towards a more globalised state, communicating effectively with one another has become more important than ever. Be it for business or leisure, the goal in a conversation is to get the message across. That being said, some debate whether the world should focus on perfecting the global languages or preserve the native tongues and encourage other to learn numerous languages.

In the Treaty on European Union (EU 2012) it is recommended that every EU citizen should learn two languages besides the native language. As the treaty itself states, “respect for linguistic diversity is a fundamental value of the EU, as are respect for the person and openness towards other cultures” (EU 2012; Majhanovich and Deyrich 2017). The European Union is composed of countries which contribute to the total of 24 official languages that vary greatly from one another along with numerous Regional and Minority Languages. In addition to this, since there has been an increase in migrants entering the continent, the diversity in language keeps increasing as these migrants might not have any working knowledge of the official languages.

In such a scenario, it stands to reason, and sources agree, that one of the benefits of language learning is social inclusion. As verbal communication is a main driver in order to have a functional conversation between two individuals, the importance of language learning is imperative. Any person that requires some form of information needs people to understand what they are asking, and the others want to make sure that they are understanding the information given.

In a separate study, Anita Vukovic (2013) explored language experience in relation to how expatriates adapt to their new host country. This study was conducted in Malta. Aptly titled Experience Language, Understanding Culture: Expatriate Adjustment on Mainland Malta, the study aimed to identify whether or not learning Maltese affected the experiences of individuals who have moved to Malta in approximately the last 20 years. Unlike many European countries, Malta has English as an official language and the vast majority of natives speak English very well, so at face value, expatriates do tend to overcome the communication barrier relatively easily.

In her article, Vukovic describes the initial ‘honeymoon’ period, where an expatriate is still fascinated by the new surroundings, then many tend to experience a ‘crisis’ period that at times may be a “hostile and aggressive attitude” towards the host country that may be caused by the perceived isolation from a dissatisfied social life. In addition, certain animosity could than be attributed to “the strange behaviour of the Others” (Richards n.d. ; Vukovic 2013) and since there is such a perception, a division might be created over time between natives and expatriates.

With this in mind, whilst one understands the culture shock someone experiences when moving to another country, one also should shed light on the fact that “transitioning from strangeness to familiarity” (Vukovic 2013) takes time. Vukovic talks about “a bicultural identity”, which follows on the argument mentioned earlier on regarding active social inclusion. The idea of bicultural identity is that of not only adjusting to the new culture of the country, but to also be able to enjoy it, and language learning just so happens to be a “commonality derived through shared identity”. Thus by knowing the host nationals and oneself in the context of the host culture, effectively putting [one] on the path to “culture shock recovery” (Oberg, n.d. ; Vukovic 2013).

Another point mentioned by Majhanovich and Deyrich (2017) is the link between language learning and economic benefits of any particular host country as well as economic success to a person with workable knowledge of a number of languages. “In this ethnically highly diverse context, it is important to foster social inclusion and active citizen participation if the European Union is to function democratically in a peaceful fashion and be economically successful” (INCLUDE 2014; Majhanovich and Deyrich 2017). Apart from this, as we are living in a rather non-liberalist era, for some, language learning is not just a means to active inclusion of citizens, but it also “represents an asset in terms of human capital; this perspective holds that knowledge of certain languages will enhance possibilities of employability in the labour market” (Majhanovich and Deyrich, 2017).

“We need to learn how to prepare people with the language skills they need for a multilingual society, and how to train people to develop the necessary sensitivity towards the cultural and linguistic needs of their fellow citizens” (King 2018). This is a statement in a report titled The Impact of Multilingualism on Global Education and Language Learning published by the University of Cambridge. Whislt this report was mostly based on what is called “the language of schooling” – the academic language used in various subjects when teaching – there are some good points regarding the benefits of language learning from the business and cultural side of things. In this report, King also mentions that globalisation increases multilingual vitality and argues against the idea of ‘one language one nation’.

A similar argument is also brought up in the EU Multilingualism Policy where it states that, “the European Union supports multilingualism as part of the cultural heritage of its citizens and nations, and has developed a number of policies supporting multilingualism, based on shared beliefs about the benefits of a multilingual and linguistically diverse society” (EU 20??; King 2018). The European Commission also states that, “language is the most direct expression of culture; it is what makes us human and what gives each of us a sense of identity” (European Commission 2005). This is corroborated by several researchers in Europe and beyond , as they agree that language is closely linked to culture. “Languages are conduits of human heritage” (Nuwer 2014).

As writing is a relatively recent development in the history of how we communicate, and many minority languages do not have a set writing system . This means that the language only exists verbally “so language itself is often the only way to convey [traditions]” (Nuwer 2014). Some even go further in saying that languages are like a verbal “ecosystem” – “an accumulated body of knowledge”; “no culture has a monopoly on human genius […] we lose ancient knowledge if we lose languages.” (Harrison 2014; Nuwer 2014).

The argument as to whether one should learn a language or not seems to side on the idea that one cannot simply get by with one language, if some argue that it is not easy to explain this to a global language speaker. Many sources mention the benefits of language learning, and the fact that globalisation seems to be increasing the demand for nations to be more multilingual implies that people should definitely be encouraged to learn more.

Teaching Methods and Best Practices

Multilingualism is becoming a mainstream as the world progresses. Be it for trade, employment or simply a conversation between a native and a tourist, it is clear that knowing another language besides one’s native tongue can give you an advantage in many aspects of verbal communication.

As this is the case, different countries have explored numerous teaching methods in attempt to find the best possible one for different age groups. In the past, it was believed that the best method of language teaching is through ‘monolingualism’ – using exclusively one language in the classroom during the whole language lesson. In essence, the monolingual principle “emphasises the instructional use of the target language to the exclusion of students’ home language, with the goal of enabling learners to think in the target language with minimal interference from the home language” (Howatt 1984). Whilst in theory, such a method is not in itself bad as it has been used for a long time, one has to bear in mind that in some cases, an international classroom might have more difficulty following as not all languages correlate to others.

This has been a debate between TESOL for various reasons, one of which being that although the monolingual principle was effective, it might result in “[perpetuating] […] students’ L1 to invisibility in the classroom” (Cook 2001; Cummins 2011). That being said, Cook does not omit the use of the target language completely. In fact, he does argue regarding

judicious use of the L1 in the teaching of second and foreign languages but cautions that despite that legitimacy of using the L1 under certain conditions, ‘it is clearly useful to employ large quantities of the L2, everything else being equal.

(Cook, 2001; Cummins, 2011)

In light of this observation, it brings to mind the concept of ‘translanguaging’ (García 2008). Translanguaging is the idea of teaching a new language by building on the learner’s pre-existing knowledge. Cummins uses English language learners as an example, but it can be applied to other languages as well: “because […] language learners’ prior knowledge is encoded in their L1, particularly in the early stages of […] learning, activation and building on prior knowledge the linking of [the target language] with the learners’ L1 cognitive schemata” (Lucas & Katz 1994; Cummins 2001, 2007; García 2008). “This cannot be done effectively if students’ L1 is banished from the classroom” (Cummins 2011). A very valid point indeed. In addition to the aforementioned, an individual who is bi-lingual (such as many Maltese people) tend to develop translation skills at an early age, hence, translanguaging would be very effective when learning a new language. According to Malakoff and Hakuta (1991), “translation provides an easy avenue to enhance linguistic awareness […] in bilingualism, particularly for minority bi-lingual children” (Malakoff &Hakuta 1991; Cummins 2011). Another valid suggestion, also by Malakoff and Hakuta (1991) is that of “encouraging newcomer students to write in their L1 and working with peer, community or instructional resource people to translate L1 writing into English, scaffolds students’ output in English and enables them to use higher order and critical thinking skills” (Malakoff &Hakuta 1992; Cummins 2011). This involves a lot of collaboration and knowledge sharing.

The INCLUDE project – a project ran by the European Commission between 2007 and 2013 – was launched in attempt to study and implement new pedagogical techniques that actively involve knowledge sharing between groups of students, as part of social inclusion. A number of case studies were conducted in France, Lithuania, Italy, Spain and the UK, investigating how language learning was being done. Amongst many findings, it was determined that the use of Content Integrated Language Learning (CLIL) return different results depending on a number of reasons. These include:

- CLIL for teenagers is more often used and analysed than CLIL for younger children.

- The usage of CLIL is less frequently discussed in language training programmes for adults who do not participate in formal education.

- The language proficiency level is decisive for migrants’ integration into the host society and also for their employability.

- Integration is an energy- and time-consuming process. It needs continuous effort from both the migrant and minority communities and the authorities and other related associations and organisations.

Similar results returned in the INCLUDE project are also seen in other studies. Whilst the above-mentioned practices are mostly applied for children, one should keep in mind the adult learner as well. One should note, that although people of all ages can learn a language successfully, not all teaching methods work for all ages.

Morice (2016) discusses the different forms of learning with particular importance to non-formal learning and how adults seem to find it to be a more effective way of learning. Firstly, because some might be faced with a number of barriers which include “financial barriers, lack of support for childcare and other caring responsibilities, lack of accessible advice and guidance to appropriate provision” (Morice 2016). Moreover, especially when it comes to migrants of poor backgrounds, it may be difficult to adapt to a formal classroom environment. However, “community-based and non-formal approaches such as learning through rhyme, singing, cookery groups and one-to-one mentoring […] are likely to be more effective in engaging and supporting this group acquire language”(Morice 2016).

When it comes to language learning and adults, it is often the case that they would opt for classes as they have spefic demands. Whether they are natives wanting to improve their literacy or migrants seeking to learn a new language, the primary goal is often “to increase employability [and/or] formal education opportunities” (Finn Miller 2010). With that in mind, as mentioned earlier by Morice (2016), when it comes to teaching adults, “experiential learning” is more effective as the learners are actively involved. (Dewey, 1938; Finn Miller, 2010).

The concept of ‘learning by doing’ had proven to be a very effective method since the early 30s. When involving the learner in the task as opposed to dictating instructions, the learners are more likely to absorb what is being taught. According to Freire (1970) he “insist[s] that learners’ lives and issues must always be the content of literacy instruction” as that way the learners can resonate with it more. Following on this, Finn Miller (2010) continues by exploring different forms of engaged instructional approaches, namely: task-based learning; project-based learning and problem-based learning.

All three approaches share a number of characteristics which include real-life contextual content, some form of interactive communication is required, makes use of all the language modularities and an end result is to be created by the end of the task – could be an answer to a question, a development of a product, or a combination. (Finn Miller 2010).

As sources suggest, when provided with real-life contextualised content, the learners are more likely to engage with it. This was something that the INCLUDE project strived to achieve. CLIL is a language policy that is “unique and different from bilingual or immersion education and a host of alternatives and variations such as content-based language learning, English of Special Purposes, plurilingual education, etc.” (Coyle 2008; Cenoz, Genessee & Gorter 2014), “a dual-focused educational approached in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language” (Coyle 2010; Cenoz, Genessee & Gorter 2014).

In spite of this, Cenoz et al.(2014) do point out that although CLIL is indeed a good form of language learning, there is still no clear definition as to what it constitutes CLIL in the first place. This is something that Majhanovich and Deyrich (2017) also discuss in their report. In Cenoz et al.’s article they outline a number of descriptions:

“Some scholars view CLIL largely in terms of the actual instructional techniques and practices used in classrooms to promote L2/foreign language learning” (Ball & Lindsay 2010; Hüttner & Rieder-Bünemann, 2010). Indeed, the conceptualisation of CLIL as ‘essentially methodological’ (Marsh 2008), ‘a pedagogic tool’ (Coyle 2002), or ‘an innovative methodological approach’ (Eurydice 2006) is widespread. Yet, other scholars consider CLIL in largely curricular terms (Langé 2007; Navés & Victori 2010). Baetens Beardsmore (2002), for example, explains that CLIL is flexible regarding curricular design and timetable organisation ‘ranging from early total, early partial, late immersion type programs, to modular subject-determined slots’. A conceptualisation of CLIL with reference to curriculum is complicated further insofar as the link between language and content can take the form of a theme or a project and does not necessarily mean the use of an additional language as the medium of instruction for a whole school subject, as pointed out by (Coyle, 2007). Finally, yet another conceptualisation of CLIL refers to it in largely theoretical terms as the interplay of the theoretical foundations of constructivism and L2 acquisition (Marsh & Frigols 2013).

Similarly, Majhanovich & Deyrich (2017) later would say that CLIL is “a generic term to describe all types of provision in which a second language […] is used to teach certain subjects in the curriculum other than language lessons themselves” (Eurydice 2006; Majhanovich & Deyrich 2017). This brings any person to think how innovative CLIL really is or whether in reality it is simply another form of content-based language instruction method of teaching.

In summary, [experts] have sought to show that the scope of CLIL is not clear-cut and, as a consequence, its core features cannot be clearly identified. [Experts] would argue that this lack of precision makes it difficult for CLIL to evolve in Europe in a pedagogically coherent fashion and for research to play a critical role in its evolution.

(Cenoz, et al. 2014)

Teaching methods are not a template that work in all situations so it has to be taken case by case. Despite this, there are numerous learning resources that cater for various groups, whether young or old. They all “focus on the goals […] target langauges, the balance between content and language instruction” (Cenoz, et al. 2014). Such teaching methods, including CLIL and other content-based language instruction have undergone important developments in the last 20 years and have become useful constructs for promoting seconds language learning and foreign language teaching.

Language Learning and Adults

In 2016, the National Statistics Office (NSO), published the results of the latest Adult Education Survey, where its main aim was to get a better picture of how many people, aged between 25 and 64 years, received formal and non-formal education, and the general perception of it. One of the modules of this survey was languages and what the general picture of language proficiency of the island is.

To start off, through this survey, it was determined that 19.3% of the total population aged 25 and 64 years have sought some form of information regarding different forms of training possibilities, which in turn implies that adults are interested in furthering their knowledge well after they finish school. Also, 7.2% are enrolling (or are currently enrolled) in formal education programs. The main reason for this, according to survey data is to increase employment opportunities, as well as, “to increase skills/knowledge in a subject of interest, with 92.3% of formal education participants confirming this” (NSO 2016). In spite of this, there were numerous participants who were following some form of non-formal education activity (33.8% of the target population). “On average, a [non-formal education] participant followed 2.34 NFE activities during the reference year.’ (NSO, 2016).

Such numbers are worth looking into as this means that adults are indeed interested in attending classes, regardless if it is formal or informal. As discussed in a previous section, EPALE (2016) has also published an article discussing the benefits of non-formal language learning for adult migrants and the reason behind it.

[As] language is a key to opening doors to much wider social benefits’, […] [it] poses a key question for adult educators and policy makers; if this is the case, […] what can be done about it? Migrants are not all the same, people migrate for a variety of reasons […].

(EPALE 2016)

With this in mind, one can also see why many adult learners go for NFE programs as opposed to formal education programs. Some may encounter barriers: financial limitations, lack of support for childcare and lack of proper guidance amongst others. Formal education very often requires commitment and time, and in some cases it can be pricey. Non-formal education programs, however, can be more versatile, and in some cases it is completely free. In recent years, the Ministry of Education and Employment in Malta has also recognized such needs and also is aware that language learning is ‘essential for economic competitiveness and inclusive societies’ (Eurydice 2018).

That being said, sources are indeed available but the question remains: are people making use of them as much as one would expect? In the Adult Education Survey of 2016, it was indeed determined that the vast majority is familiar with two other languages besides their mother tongue, but as to whether they have made use of the resources provided by the state, is yet to be determined. In addition, many are aware of the limited use of the Maltese as a language. Whilst migrants affirm that learning Maltese may help in interacting better with locals, they still opt for a more global language, or a more wide-spoken language.

Such a scenario is all across Europe. In the Special Eurobarometer 386 (EC 2012), respondents were asked to name two other languages, apart from their mother tongue, that they believed to be most useful for their personal development. As expected, English was the one most voted for, and was followed by German (17%), which is the most spoken language in Europe as a mother tongue, followed by French (16%) (EC 2012). An interesting perception emerged in this survey – “around one in eight Europeans (12%) do not think any language is useful for their personal development’ (EC 2012). One could see this as odd, especially when considering Europe is very linguistically diverse.

In this Eurobarometer Survey (2012), respondents were asked in what ways can someone be encouraged to learn a new language. In essence “Europeans are more likely to think that free lessons are the best incentive to learning and improving language skills” (EC, 2012). Moreover, 19% of the respondents claim that people would be further encouraged if they are paid to learn. With that said, there was also a mention of learning resources that fit their schedule would encourage them to learn a language (around 16%). This is a barrier that many migrants often come across when it comes to learning as mentioned earlier on. Interestingly, the respondents think that televised or internet courses would encourage people when it comes to learning as they are very easily accessed, with the exception of Malta:

[it] is the only country [that showed] a sizeable change [in comparison to the previous survey] in opinion on the availability of good courses on television or the radio increasing the likelihood of learning or improving language skills, and it is now a less widely held view.

(EC 2012)

One other thing that emerged from this survey is the different perceptions of language learning between different age groups. Younger groups recognise the benefits of language learning. The 20+ age group in particular showed more interest in learning in comparison to the 15+. The reason could be the fact that the 20+ age group finished school at a later stage, hence there is more willingness to study autonomously. In fact the learning methods chosen require a certain level of self-initiative: ‘the availability of good internet courses’, ‘opportunity to learn it in the country where the language is spoken’ and ‘finding a course that suits a personal schedule’ (EC 2012). In addition, active language learners where more likely to give the same reasons as opposed to those who do not.

Sources such as the Eurobarometer is a rather extensive document and offers good insight on the situation in Europe in relation to language learning. However, when it comes to the family unit, there is not much information. When it comes to language learning and the family unit, data sources are slightly limited. That said, through data collected from language surveys and compared to the way children learn, it may be possible to find a compromise and seek the best solution.

What are Other Countries Doing

The notion of language endangerment and fear of language extinction is something that troubles many multilingual countries and countries whose native language is not a global one. In recent years, many have shed more light on the importance of language diversity and many studies have been conducted to see the current status of numerous languages as well as for ways to revitalize languages.

As discussed in many of the sections of this literature review, the European Union prioritises language diversity very much. Considering the large number of languages present In such a small area in comparison to other continents, language has been recognized as a pillar in a nation’s culture. By 2017, the number of endangered languages in Europe exceeded 50, with many being ‘severely endangered’ – spoken only by the older generations (UNESCO 2017). In the Regional and Minority Languages in the EU report (2016), there is a section dedicated to the ‘institutional support’ for such languages, to prolong their presence and prevent extinction. Whilst it states that “local and central authorities bear the primary responsibility for [linguistic policies], […] EU bodies can support their actions and help” (EC 2016).

With that said, even though the EU linguistic policies did target minority languages, in many cases, these policies were targeted at other areas. Meaning that some policies where designed to promote something else such as culture and education. Example of this is the “decision no 1934/2000/EC on the European Year of Languages (2001)” that whilst it “did not mention RNLs, it included promotion of [specific minority languages] […]. Moreover, almost 66% of the activities in the context of that year covered RMLs and almost 40% endangered languages’ (EC 2016).

Similarly, a year later, the Council of Europe took in a resolution regarding the promotion of linguistic diversity and language learning. “It called on the Member States to provide for as diversified a language can offer in language policy as possible including regional languages, in order to promote cooperation and mobility in Europe” (EC 2016). The aim here is evident – to promote language and culture to prevent it from going extinct. However, one must also look at how each country is handling it. In a separate section – teaching practices – the present study discussed language learning techniques. However, I did not have a specific focus on any particular country’s policy. In spite of that, in many of the sources relating to language learning, it was mentioned several times that there is a difference between teaching children and adults. Children are more likely to benefit in a conventional classroom environment as opposed to adults, where non-formal language is more likely to be effective.

Back in 2002, UNESCO got together a group of linguists from around the world to assess the state of any given community language and together they come up with a framework “for determining the vitality of a language” and therefore be of and for “policy development, identification, of needs and appropriate safeguarding measures” (UNESCO 2002). The report following this study, titled Language Vitality and Endangerment, it helped in establishing a number of criteria that determine the language vitality. These are:

- Number of Speakers

- Intergenerational language transmission

- Community members’ attitudes towards their own language

- Shifts in domains of language use

- Governmental and institutional language attitudes and policies

- Type and quality of documentation

- Response to new domains and media

- Availability of materials for language education

- Literacy and proportion of speakers within the total population

“Taken together, these nine factors can determine the viability of a language, its function in society and the type of measures required for its maintenance or revitalisation” (UNESCO, 2002).

The mentioned framework was used in Australia and Venezuela. In 2005, the National Indigenous Languages Survey Report was published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. This report provided an analysis of the situation of the indigenous languages in Australia. According to this report and based on the above-mentioned criteria, the report determined that only a little over a half of the indigenous language are spoken:

only 145 [out of] […] more than 250 known indigenous languages continue to actually be spoken, […] 111 of them classified as severely or critically endangered [and] only 18 […] are described as strong according to such a crucial factor as “intergenerational transmission”.

(AIATSIS 2005; UNESCO 2005)

Similarly, in Venezuela, a language vitality assessment was concluded with a focus on three indigenous languages, Two out of the three languages seem to be in critical danger, based on the data collected from the survey, with Mapoyo being on the verge of extinction as there is no intergenerational transmission and through a writing system is in place. As for the other two, although there is language presence in various media and is passed down, from one generation to another.

Unfortunately, in both assessments, although the data collected is insightful, no plans-of-action seem to be documented. Hence, it can be said that many experts are in their data collection phase, even though the studies have been conducted a few years ago. This is a common occurrence; that of providing conclusive data, but unlike studies involving specific teaching methods, data actions relating to language revitalisation and their results do not seem to be available.

Back to the European Union, countries are encouraged to keep indigenous languages alive. Whilst data on specific countries does not seem to be available, it is worth looking at what the EU recommends for a successful language revitalisation plan. In Revitalising Endangered Languages: A Practical Guide, Penfield (2018) lays out a complete guide on what is the best approach in planning a language revitalisation project. In her words, “such a plan specifies short and long-term goals over several years and provides a structure within which to plan and implement a wide range of projects which support those goals” (Penfield, 2018). Each project would in return consist of smaller, digestible activities that help in reaching the set goals.

Penfield starts off that in order to set up a successful project one must understand what a ‘project’ is in this context. Whilst everyone has a generic idea, or rather, knows the definition of the term, that definition varies from one person to the other. She then continues by outlining a series of the steps that make the setup of a successful language revitalizing program. The steps include ideation, inventory of resources available and what is needed, plan-of-action and of course implementation. In addition, she also lists the documentation and evaluation of the project – documentation allows reflection and also room to find out whether something is returning the desired result or not.

As already mentioned, in this section as well as previous sections of this literature review, the importance of keeping languages alive is imperative, as it goes beyond day-to-day communication; it is part of culture. Also, many experts agree that knowledge of a language is beneficial to an individual in terms of employability and social inclusion amongst other things. That said, the next step should be making these revitalizsing language programs more mainstream as it encourages different countries to implement them.

Bibliography

Association for Language Learning. 2019. The fight for survival: language and identity. [online] Available at: <https://www.all-languages.org.uk/features/fight-survival-language-identity/> [Accessed 13 February 2021].

Cenoz, J., Genesee, F. and Gorter, D., 2021. Critical Analysis of CLIL: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. [online] Academic.oup.com. Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/applij/article/35/3/243/146345?login=true> [Accessed 7 March 2021].

Chauvot, P., 2016. Endangered Languages: Why are so many languages dying. [online] Communicaid.com. Available at: <https://www.communicaid.com/business-language-courses/blog/why-are-languages-dying/> [Accessed 6 March 2021].

Cummins, J., 2011. Multilingualism in the English‐language Classroom: Pedagogical Considerations. [online] Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/27785008> [Accessed 18 February 2021].

Cummins, J., 2012. Rethinking monolingual instructional strategies in multilingual classrooms. [online] Journals.lib.unb.ca. Available at: <https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/CJAL/article/view/19743> [Accessed 5 April 2021].

European Commission. 2012. EUROPEANS AND THEIR LANGUAGES. [online] Available at: <https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf> [Accessed 17 March 2021].

European Commission. 2018. EU population up to nearly 513 million on 1 January 2018. [online] Available at: <https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/9063738/3-10072018-BP-EN.pdf> [Accessed 22 February 2021].

Eurydice – European Commission. 2018. Population: Demographic Situation, Languages and Religions – Eurydice – European Commission. [online] Available at: <https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions-49_en> [Accessed 23 February 2021].

European Parliament. 2016. Regional and minority languages in the European Union. [online] Available at: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/EPRS-Briefing-589794-Regional-minority-languages-EU-FINAL.pdf> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

Finn Miller, S., 2010. Promoting Learner Engagement When Working With Adult English Language Learners. [online] Camdencountylibrary.org. Available at: <https://www.camdencountylibrary.org/sites/default/files/files/LearnerEngagement%20in%20ESL%20teaching.pdf> [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Formosa, M., 2019. Measuring and Modelling Demographic Trends in Malta: Implications for Ageing Policy. [online] Inia.org.mt. Available at: <https://www.inia.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/4.2.1-Measuring-and-Modelling-Demographic-Trends-in-Malta-pgs-78-90-Final.pdf> [Accessed 21 April 2021].

Hopkins, L., 2005. Doesn ‘t everyone speak English anyway? Multilingualism in the Age of Globalization. New Hampshire, USA: University of New Hampshire.

Macdonald, V., 2019. Malta’s population growth largest in EU – by far. [online] Times of Malta. Available at: <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/maltas-population-growth-largest-in-eu-by-far.720748> [Accessed 4 March 2021].

MEDE. 2016. A Language Policy for the Early Years in Malta and Gozo. [online] Available at: <https://education.gov.mt/en/nationalliteracyagency/Documents/Policies%20and%20Strategies/A%20Language%20Policy%20for%20the%20Early%20Years%20in%20Malta%20and%20Gozo.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

National Statistics Office. 2018. Regional Statistics[online] Available at: <https://nso.gov.mt/en/publicatons/Publications_by_Unit/Documents/02_Regional_Statistics_(Gozo_Office)/2020/Regional%20Statistics_Economy.pdf> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

National Statistics Office. 2020. Regional Statistics 2020. [online] Available at: <https://nso.gov.mt/en/publicatons/Publications_by_Unit/Documents/02_Regional_Statistics_(Gozo_Office)/2020/Regional%20Statistics_Demography%20and%20Education.pdf> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

National Statistics Office, 2021. Regional Statistics Office. [ebook] Valletta, Malta: National Statistics Office. Available at: <https://nso.gov.mt/en/publicatons/Publications_by_Unit/Documents/02_Regional_Statistics_(Gozo_Office)/Regional%20Statistics%20MALTA%202019%20Edition.pdf> [Accessed 3 March 2021].

King, L., 2018. The Impact of Multilingualism on Global Education and Language Learning. [online] Cambridgeenglish.org. Available at: <https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/Images/539682-perspectives-impact-on-multilingualism.pdf> [Accessed 17 March 2021].

Nuwer, R., 2014. Languages: Why we must save dying tongues. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20140606-why-we-must-save-dying-languages> [Accessed 28 March 2021].

Olko, J. and Sallabank, J., 2018. Revitalizing endangered languages: a practical guide. [online] Available at: <https://media.milanote.com/p/files/1L53b01X4z0p2p/0wI/Attachment_0.pdf> [Accessed 21 April 2021].

Pace, M., 2017. https://education.gov.mt/en/foreignlanguages/Documents/Foreign%20languages%20-%20The%20Malta%20Independent.pdf. The Malta Independent,.

Pasikowska-Schnass, M., 2020. European Day of Languages: Digital survival of lesser-used languages. EPRS.

Scicluna, M., 2016. Demographic trends. [online] Times of Malta. Available at: <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/Demographic-trends.613908> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

Times of Malta. 2020. 12% of children in Malta are foreigners. [online] Available at: <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/12-of-children-in-malta-foreigners.750997> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

UNESCO. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. [online] Available at: <https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183699> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

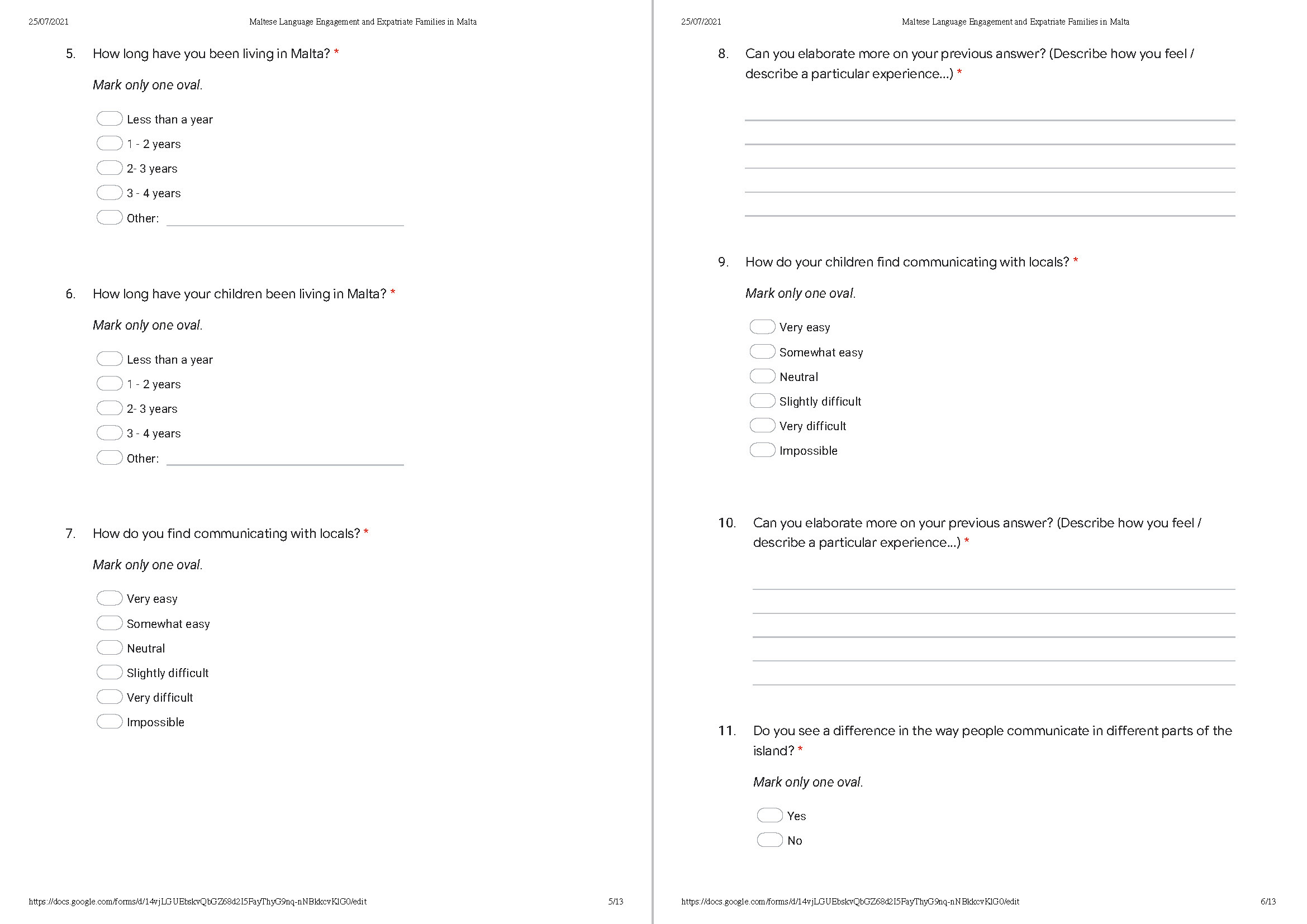

Survey Analysis

Last month, I had put together a survey aimed at expats and expats families, where I asked various questions regarding language learning, communication and social inclusion. You can see how the survey questions were collated here.

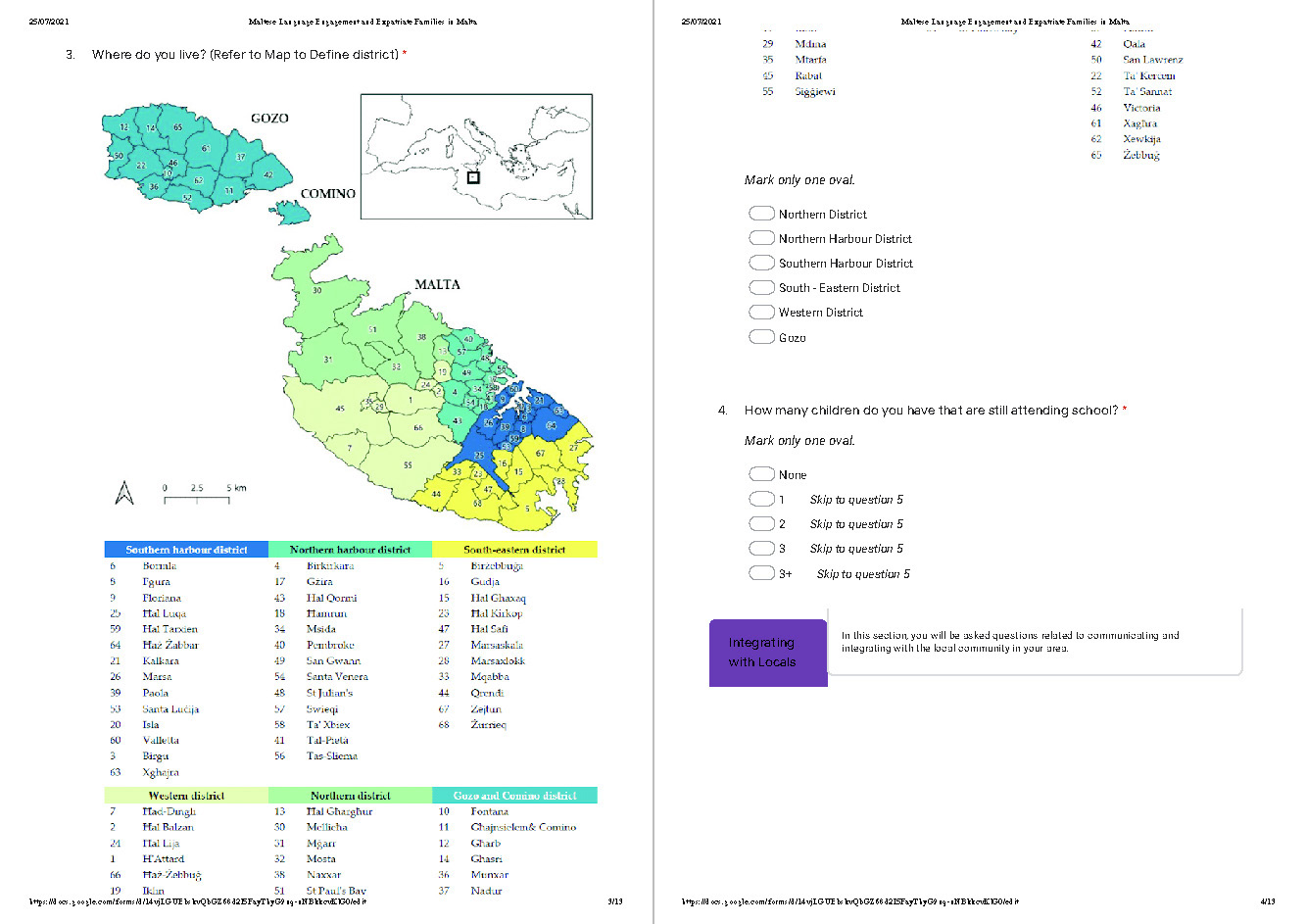

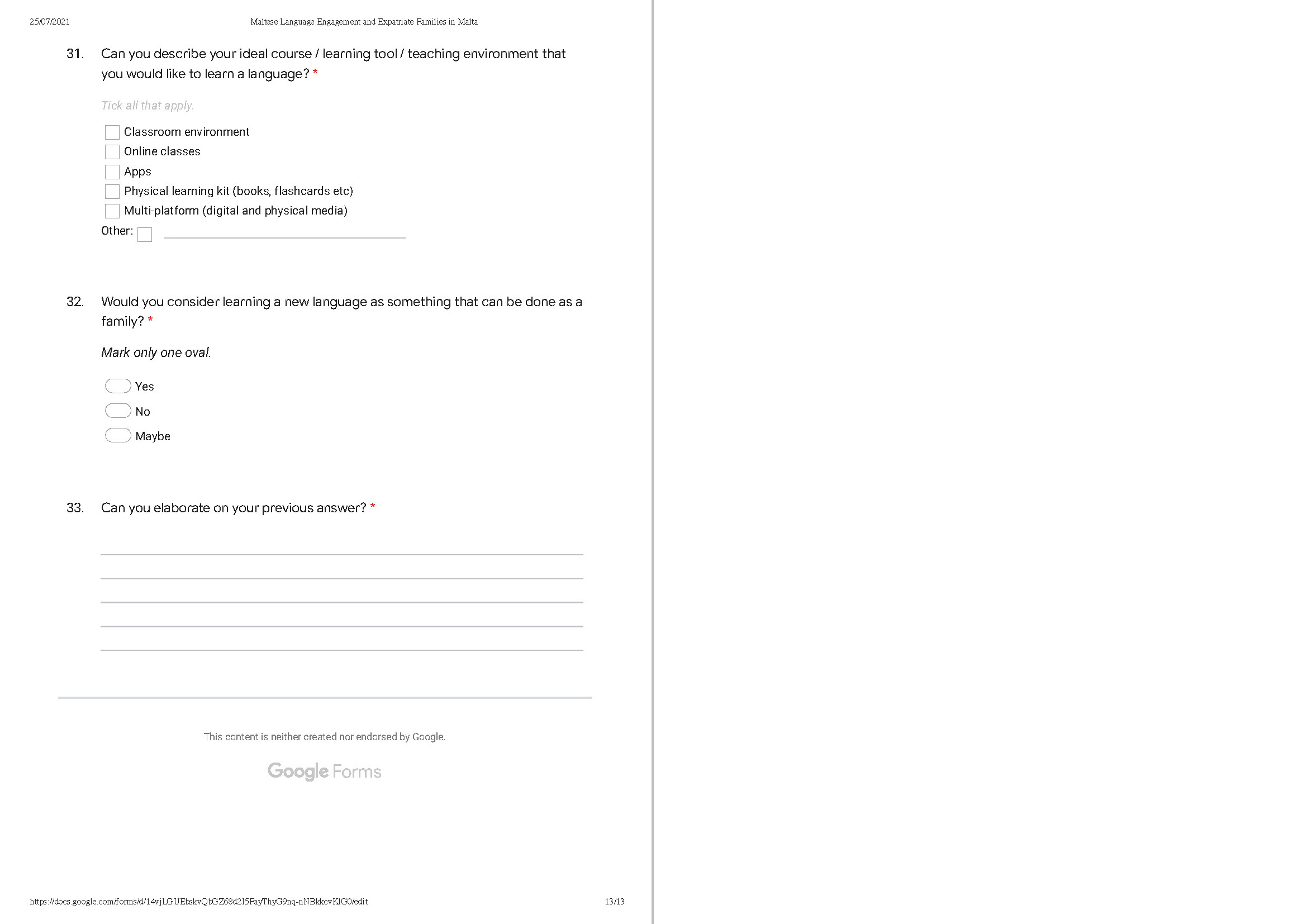

Overview

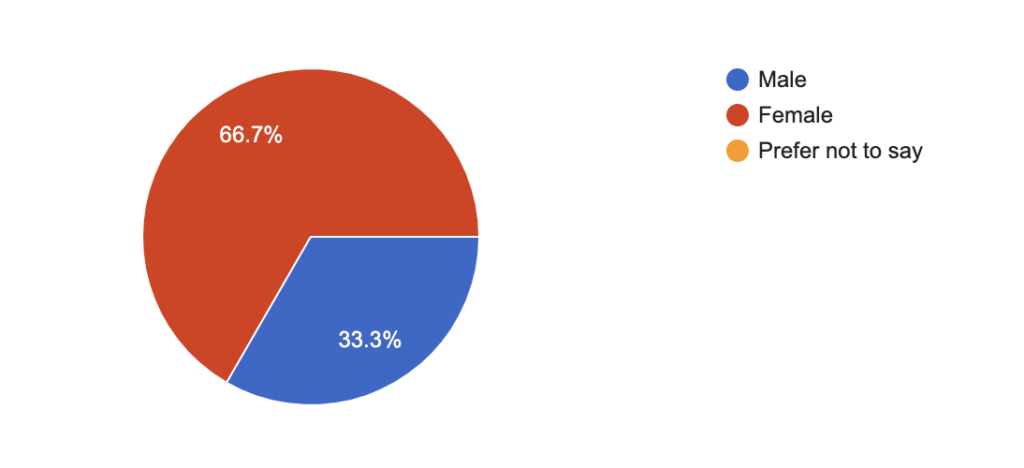

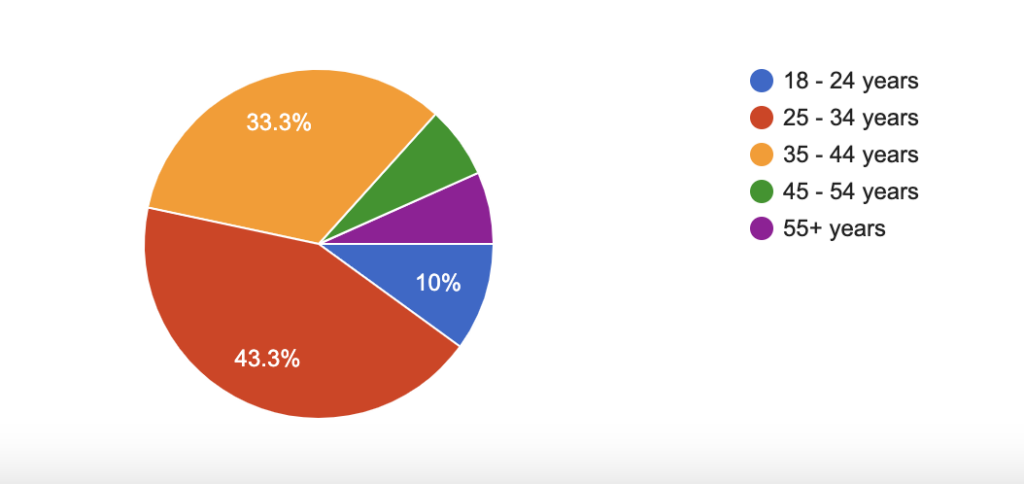

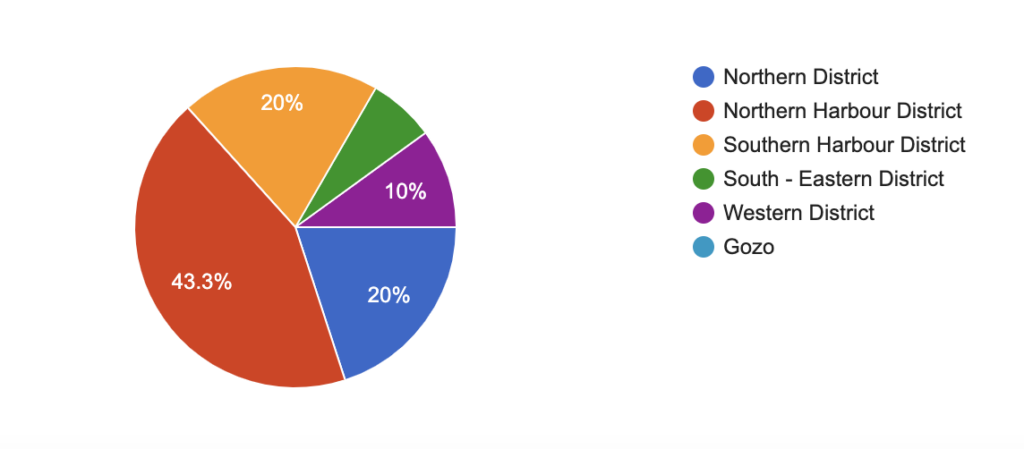

I got 30 responses in total, out of which 20 were female and 10 were male. The majority where between 25-34 years old, followed by the 35 and 44 years, 18 and24, 45 to 54, and over 55 years respectively. Also, the majority live in the Northern Harbour District, with 13 respondents out of the 30, followed by the Northern District and the Southern Harbour District – 6 respondents each, Western District – 3 respondents and lastly the South-eastern District with 2 respondents. None of the respondents were from Gozo.

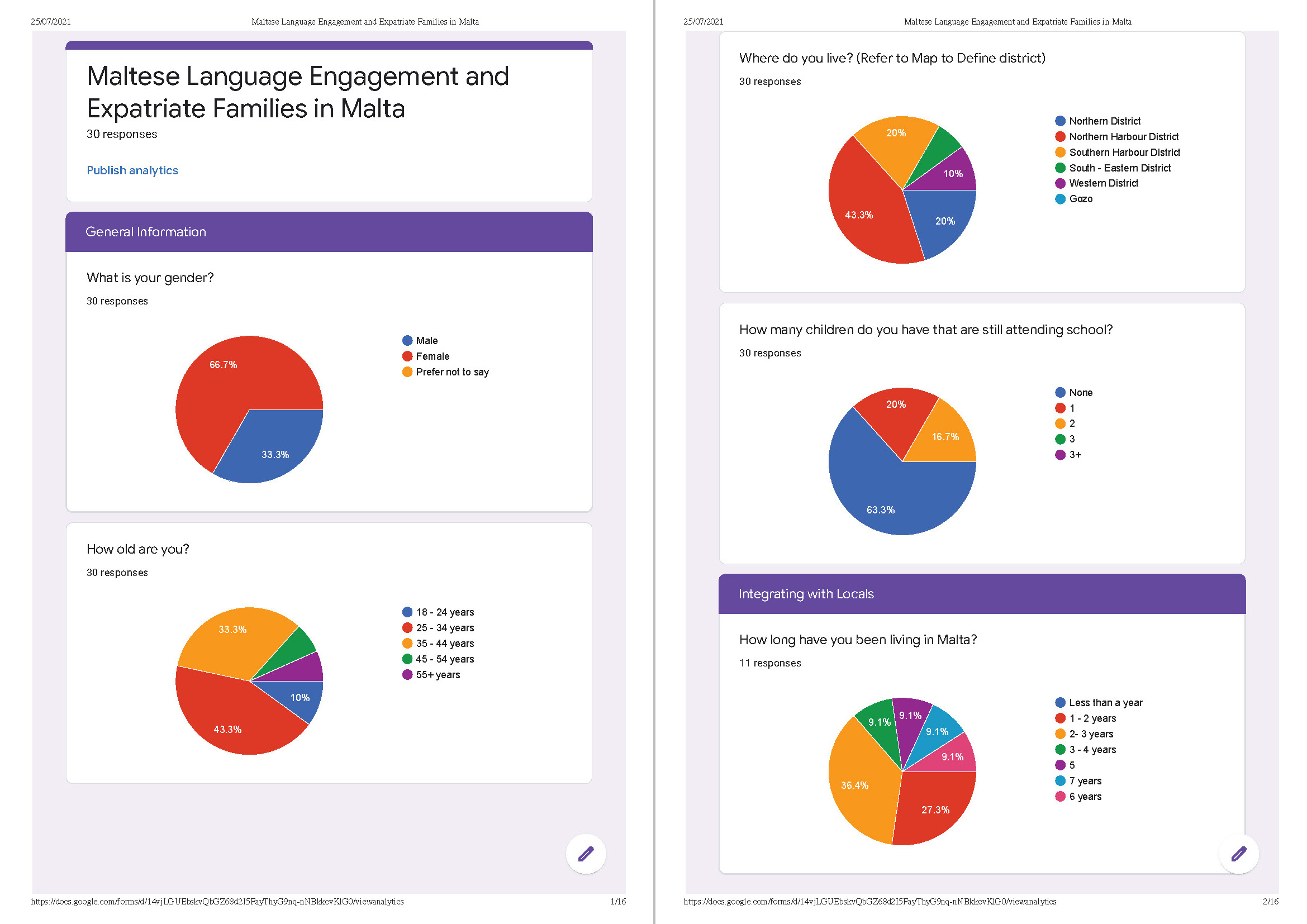

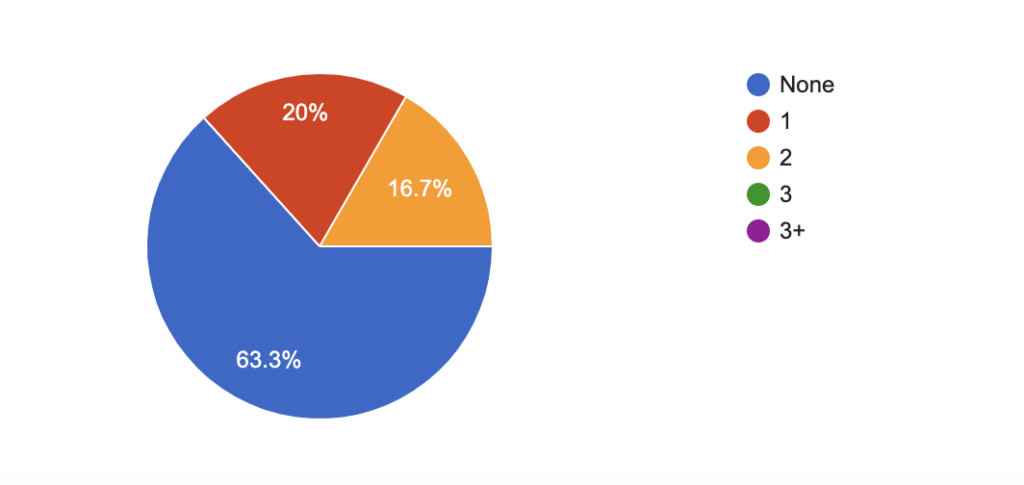

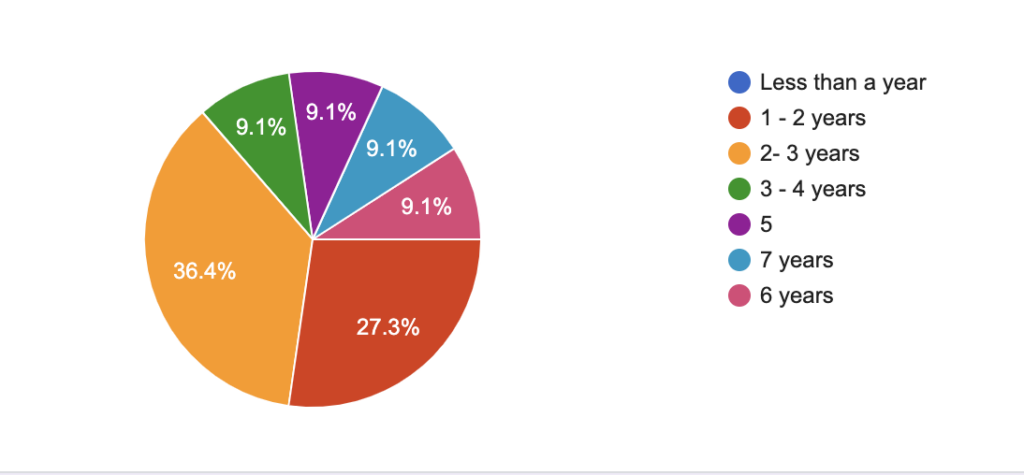

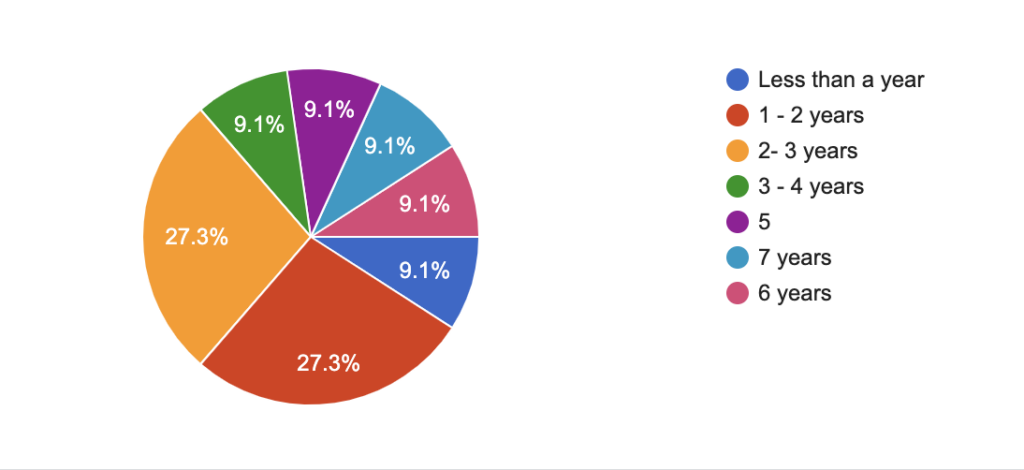

Out of the 30 respondents, only 11 respondents had children that were still attending school. 6 respondents have a child still attending school and 5 respondents have two. For the most part, the children have been living in Malta for the same amount of time as the parents (2-3 years), with the exception of 1 female respondent where she had been here for a year longer than her children.

Communicating with Locals

The respondents were asked how they find communicating with locals. They were also asked how their children find it. This section was answered by the 11 respondents that had children still attending school. The 11 respondents were all from European countries bar one, which are:

- England – 2

- France – 1

- Serbia – 1

- Portugal – 4

- Sweden – 1

- Spain – 1

- Brazil – 1

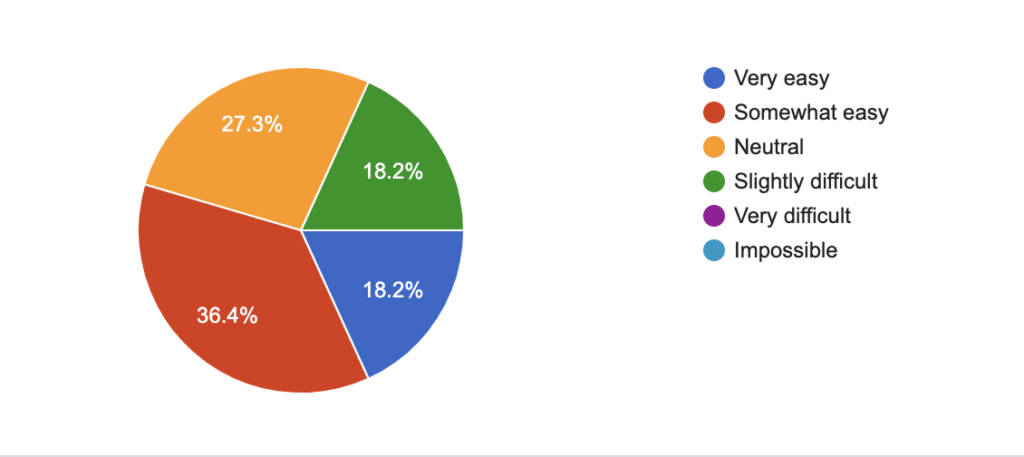

Starting off with the respondents themselves, i.e. the parents, they said that they find it ‘somewhat easy’ for the most part.

That said the age groups vary. In all age groups above 25 years of age, there are various responses. Interestingly enough all the respondents who answered ‘neutral’ are all in the 35 – 44 age group and have all been living in Malta for 1 – 2 years. Possibly it has to do with the fact that they have not been in Malta long enough. However, looking at the respondent who has been living for 6 years, she finds communicating with locals ‘slightly difficult’ and she is also in the 35 – 44 age group, whereas a respondent who had been in Malta for 7 years, says it is ‘somewhat easy for her.

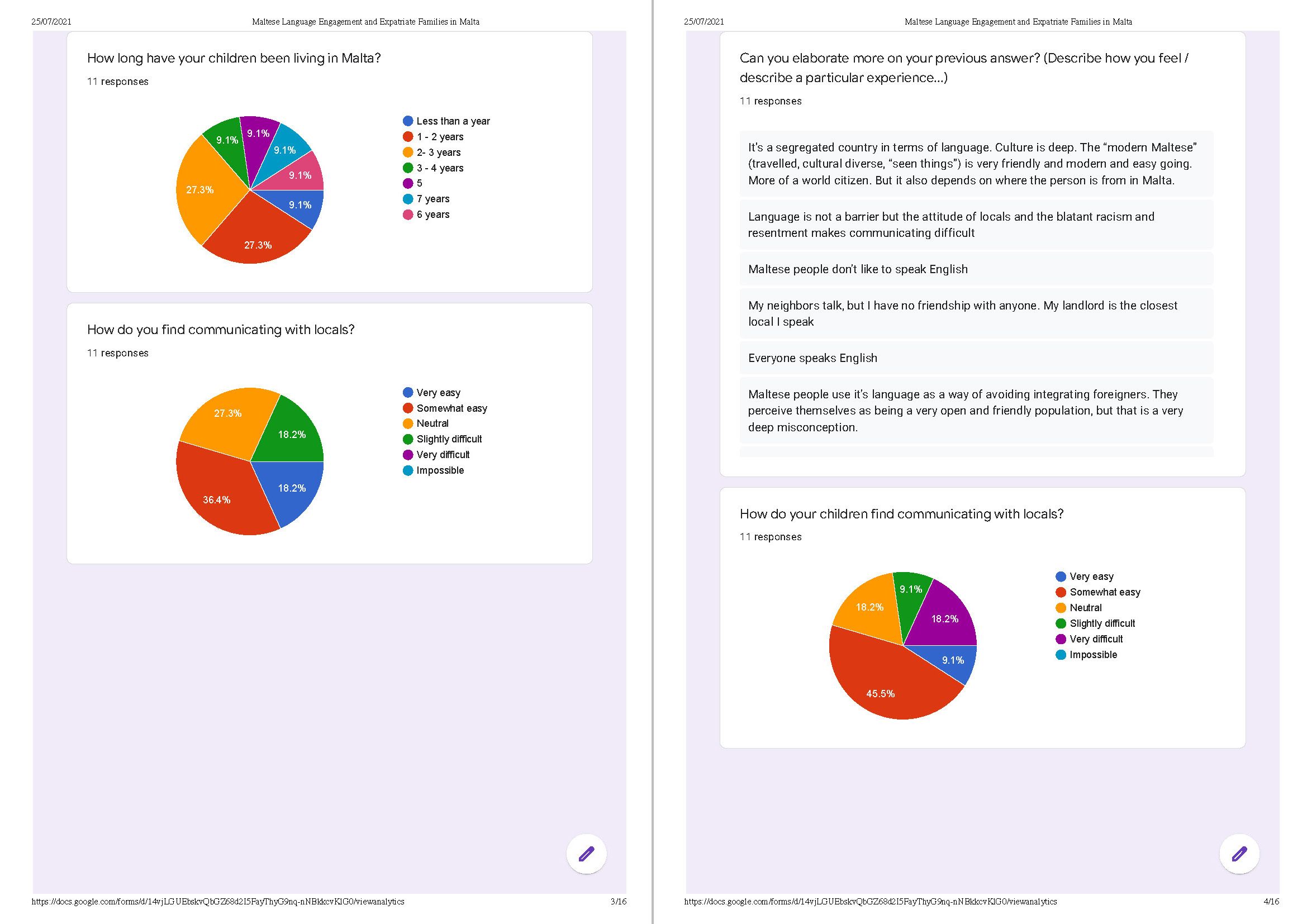

The respondents were also asked to elaborate on their answer. Reasons also varied. Some were positive, but others were rather negative. Some claimed that as English is a second language, the get along just fine when it comes to communicating with locals. Some argued that it is more of a cultural thing rather than the language itself – people tend to use English with foreigners and more formal context, whereas locals speak Maltese for more casual or private matters. The respondent who has been living here for 6 years, stated that ‘Maltese people don’t like to speak English. The one who had been in Malta for 7 years said: ‘Language is not a barrier, but the attitude of locals and the blatant racism and resentment makes communicating difficult’. This last comment did digress from the main scope of the survey, however one can take this as a culture shock or even a culture clash.

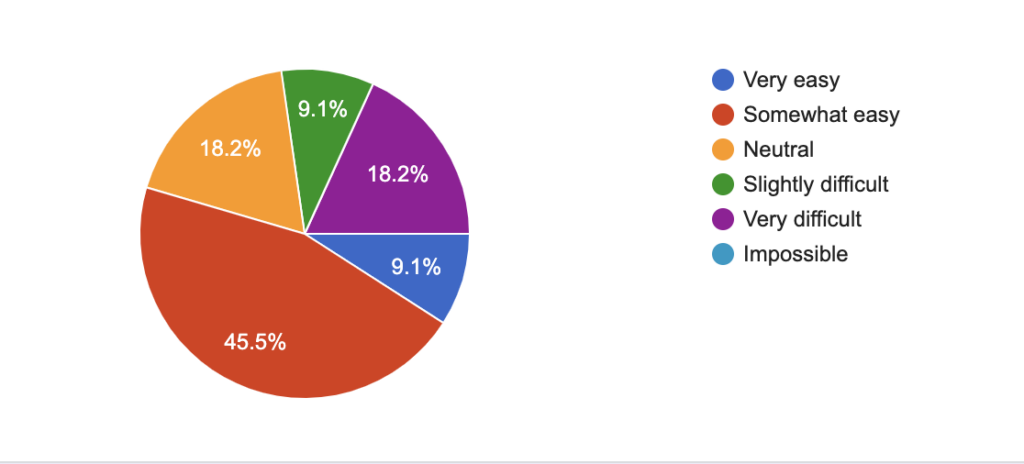

When it comes to the children, the results varied, but only slightly. The good thing is that most children find it easier to communicate with locals. One of the reasons given was that as children are more exposed to the language in school, they are more likely to pick it up. However, it was also mentioned that in some cases, children would just speak English to them. One interesting result that came out though is that there were to respondents that claimed that their children find it ‘very difficult’ to communicate with the locals – something that no adult has responded.

Lastly, the respondents were asked whether they see a difference in the way people communicate in different regions. As expected, the majority answered ‘Yes’.

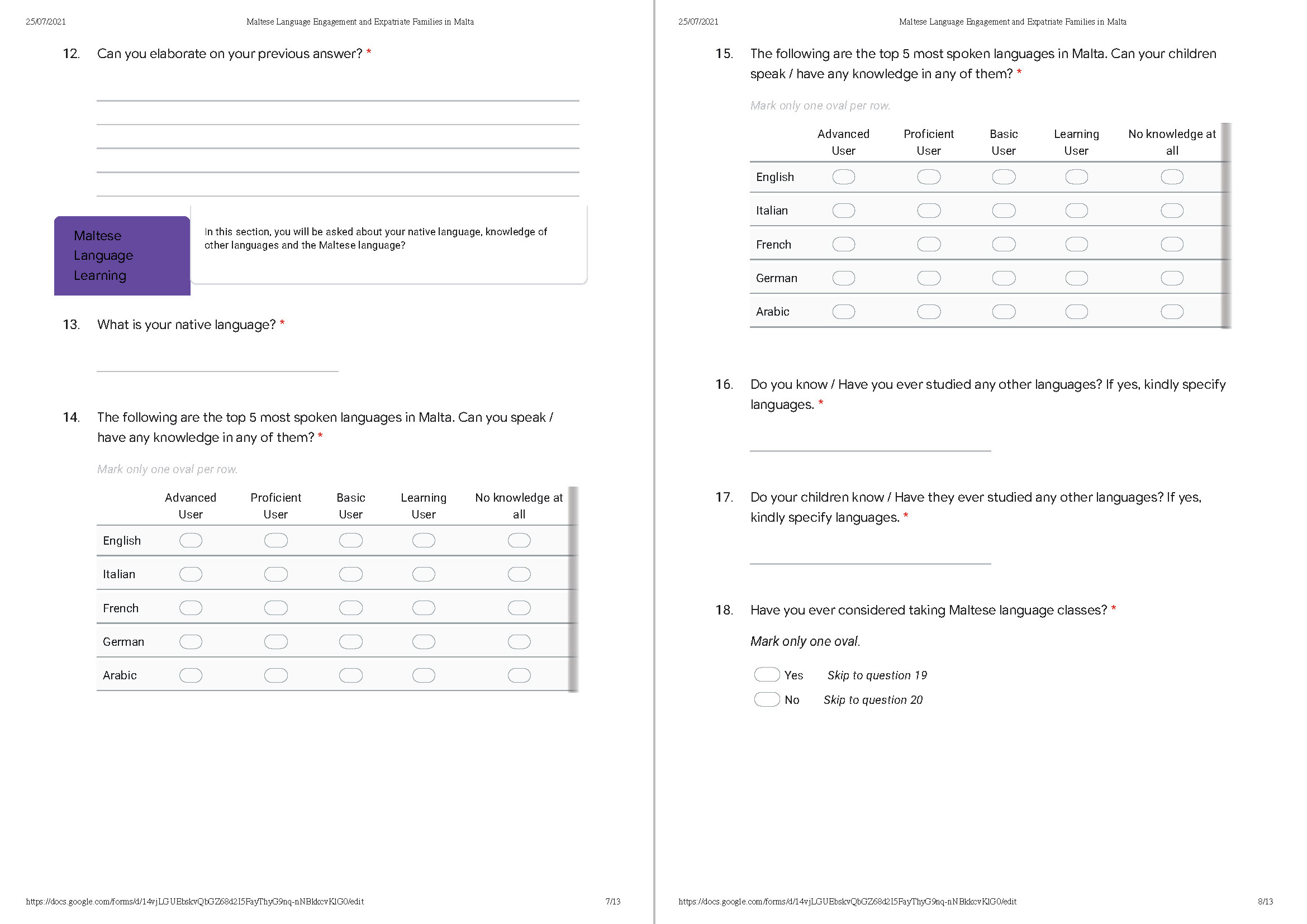

Language Proficiency

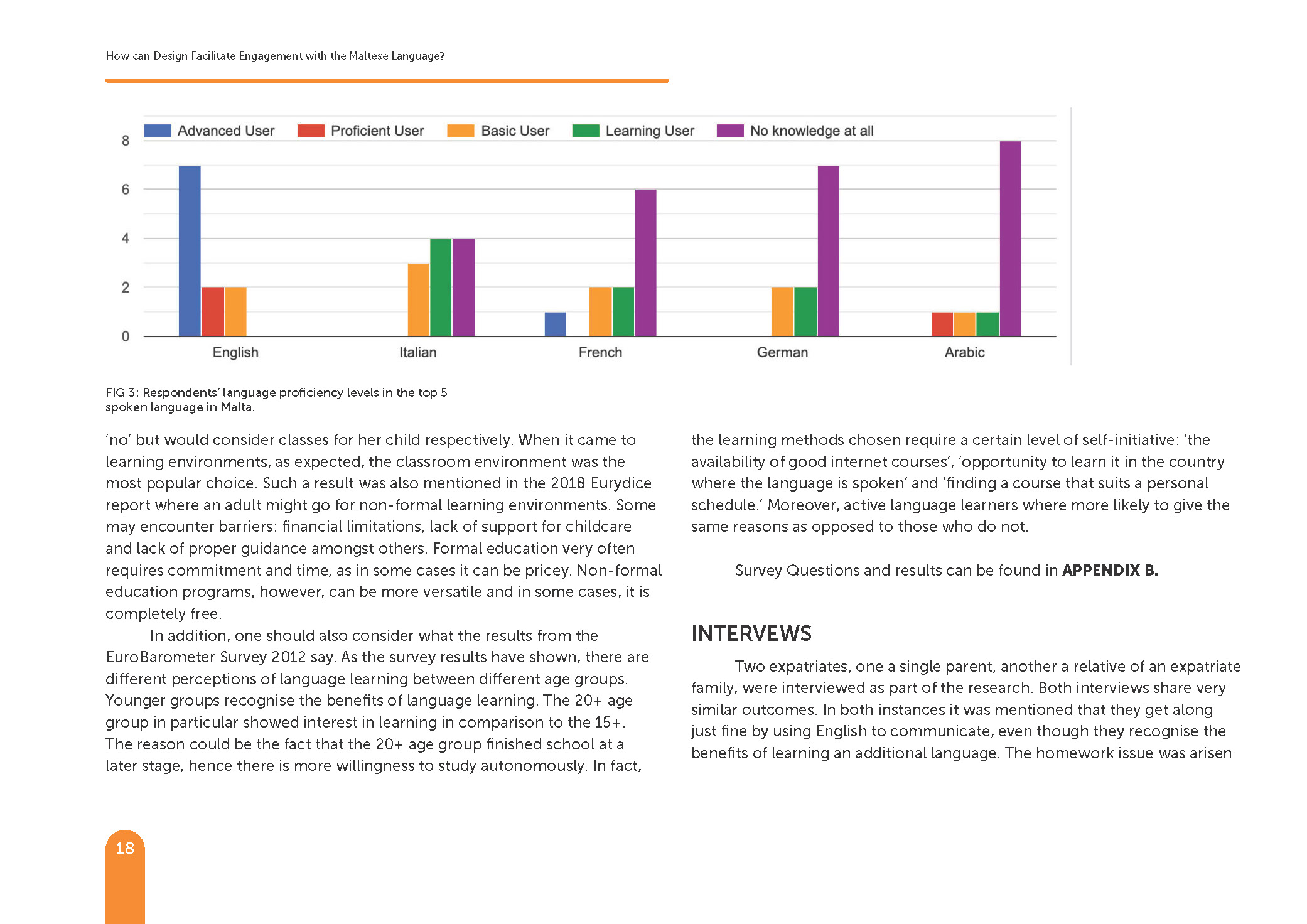

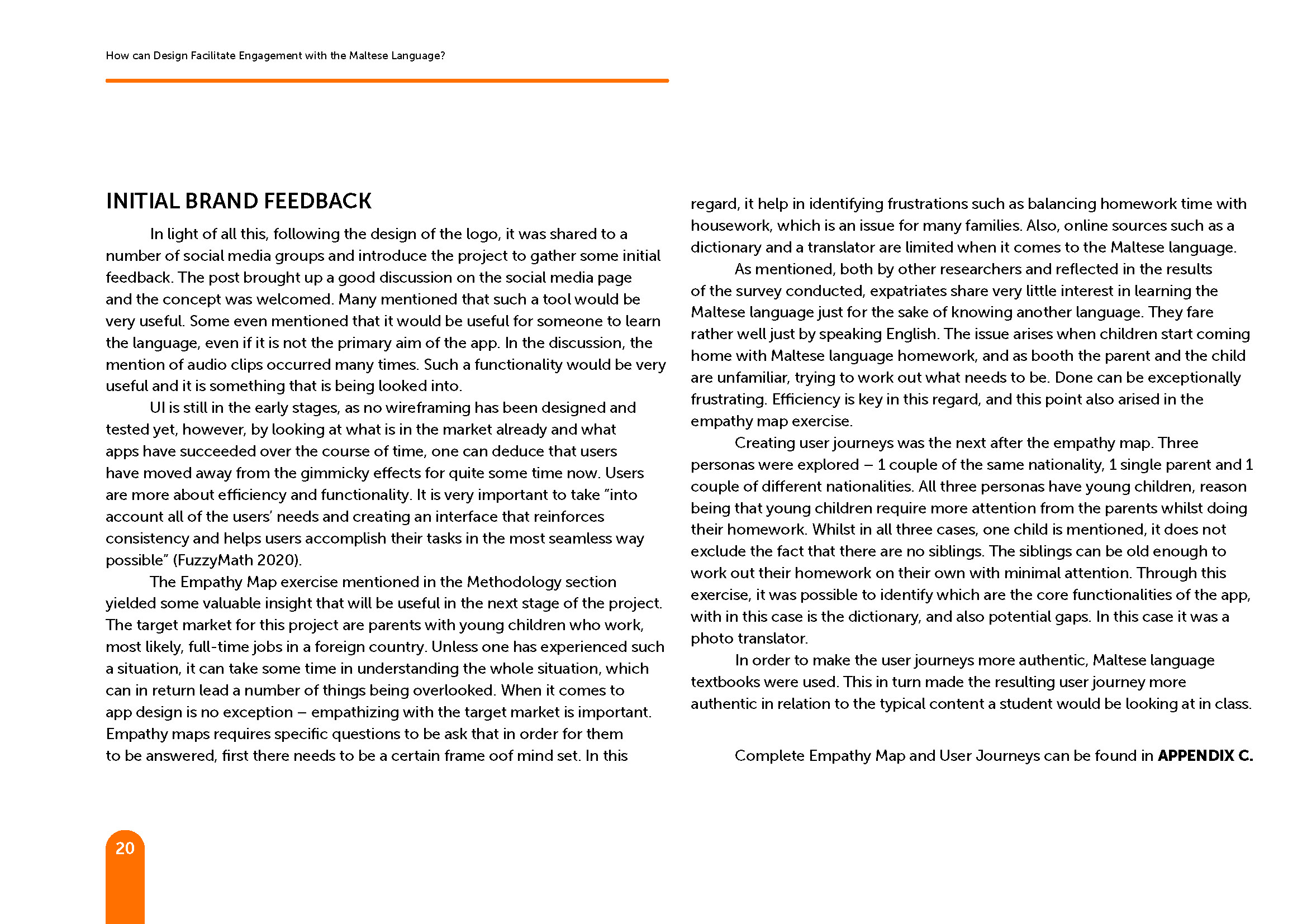

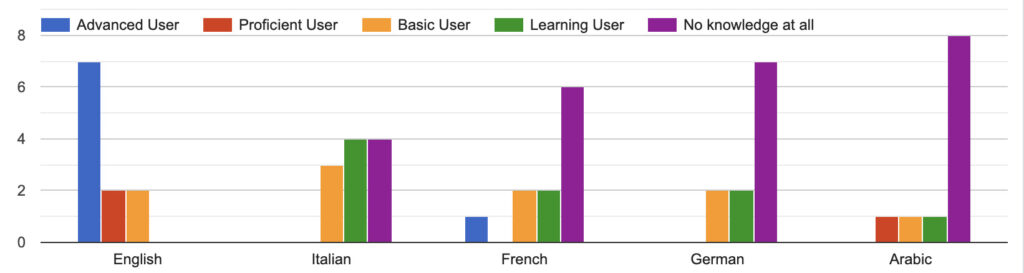

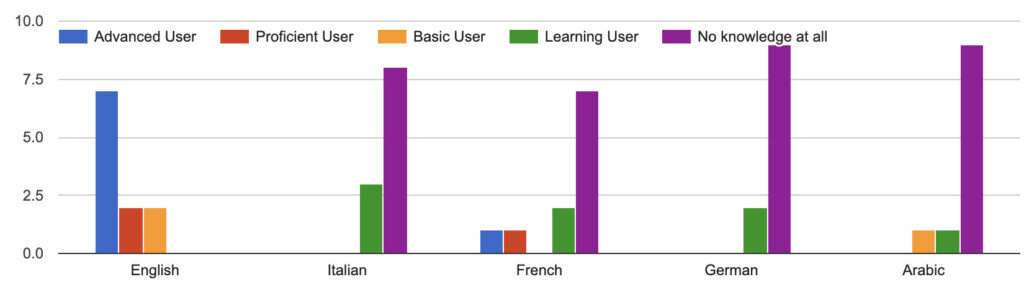

The respondents were also asked about language proficiency. As per the latest Language Survey, the respondents were asked about their level of proficiency in the top 5 foreign languages spoken in Malta. These languages are:

- English

- Italian

- French

- German

- Arabic

As expected, the highest-ranking language was English, with 7 respondents choosing ‘advanced user’, the most popular global language out of the five. The lowest were German and Arabic, with 9 respondents claiming they have ‘no knowledge at all’. With that said, the proficiency levels in the languages varied. Although all languages, bar English, had a substantial number of respondents claiming that they cannot speak it, there were respondents who have some knowledge of another language besides their mother tongue. Bearing in mind that most respondents are not native speakers of the above-mentioned languages, this data shows that people are aware that knowing an extra language is beneficial.

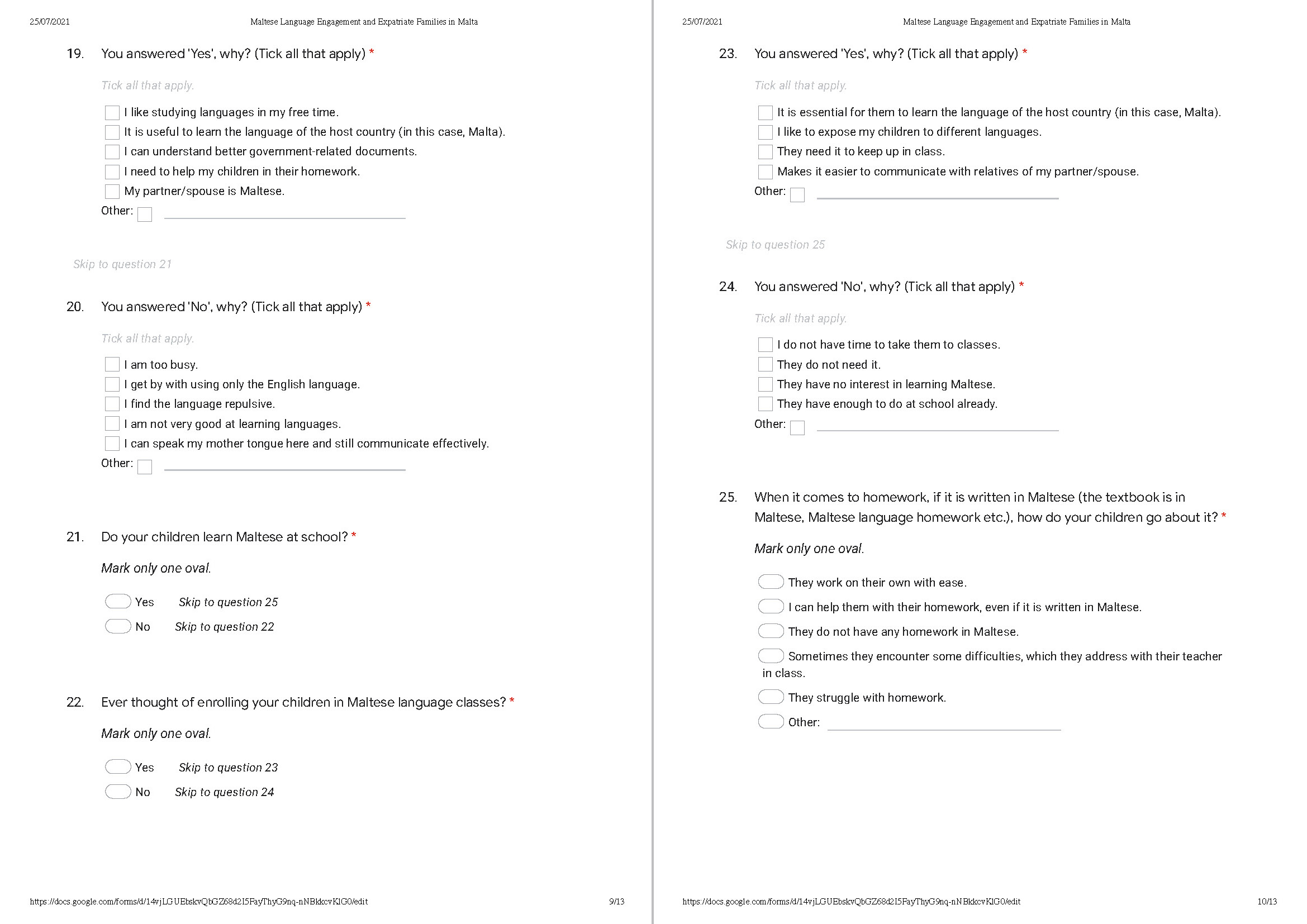

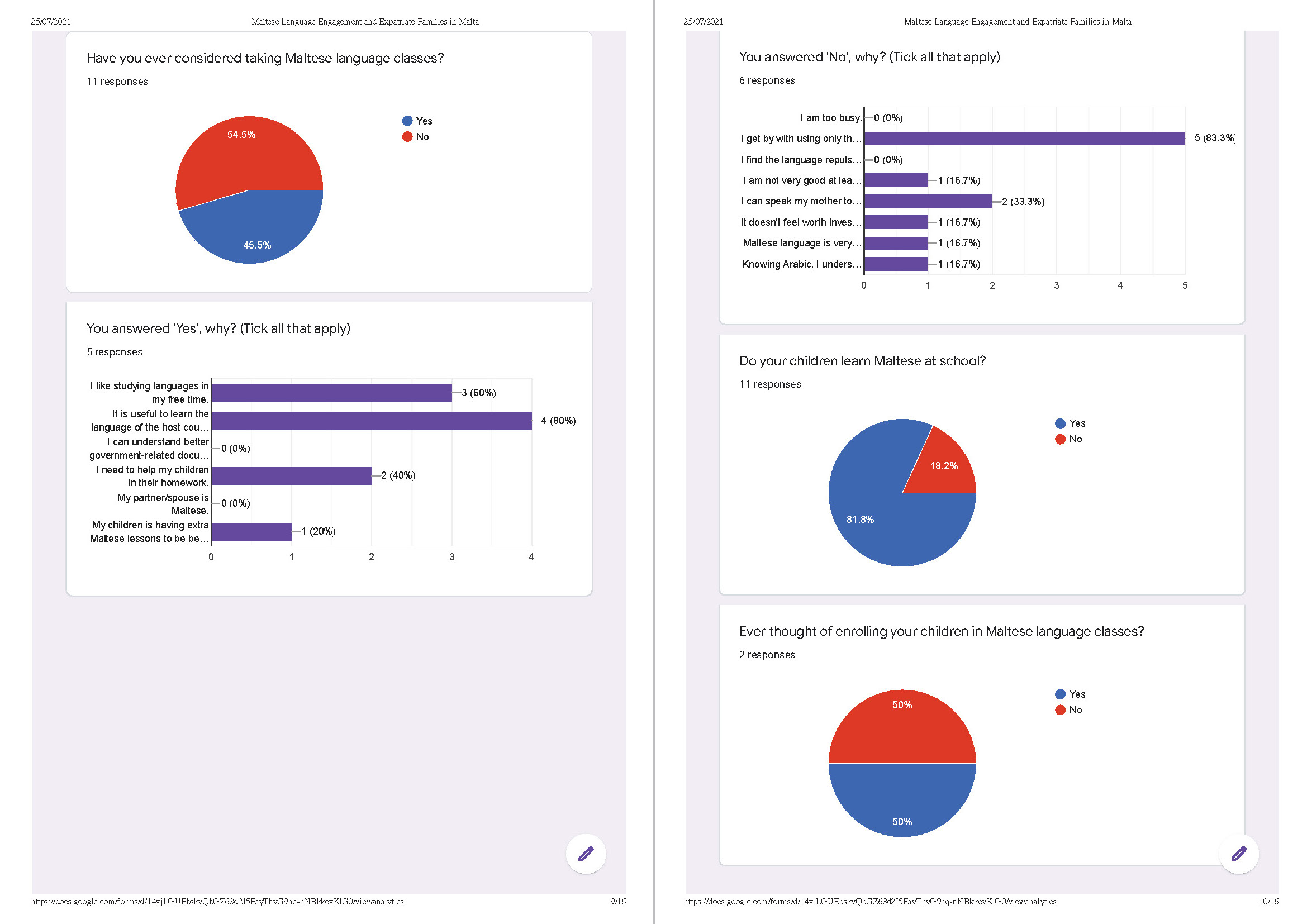

On a separate note, the respondents were asked whether they would consider learning Maltese and whether they would consider enrolling children in Maltese language classes (if not already doing so in school). Even if the majority was VERY marginal, 54.5% and 45.5%, the majority would not consider learning Maltese, as they would get by with English. In addition, some claimed that they can use their mother tongue here, others find Maltese complicated, or simply because they think that they are not good at learning languages. That said, the ones that would consider taking classes, 80% out of the ‘Yes’ group, do understand the benefits of language learning and also because it would help them with their children and homework.

Following up on the last point, when the respondents were asked about their children, the majority already have their children enrolled in Maltese language classes in school. Out of the 2 respondents that their children do not learn Maltese in school, one said that she would consider Maltese language classes for her child.

When asked about how children deal with homework, some did claim that their children struggled with their homework, however for the most part, the difficulties were addressed with the teacher in class. With that said, however, other responses included ‘they do not have Maltese language homework’ and one respondent said that she can effectively help her child with homework without difficulty.

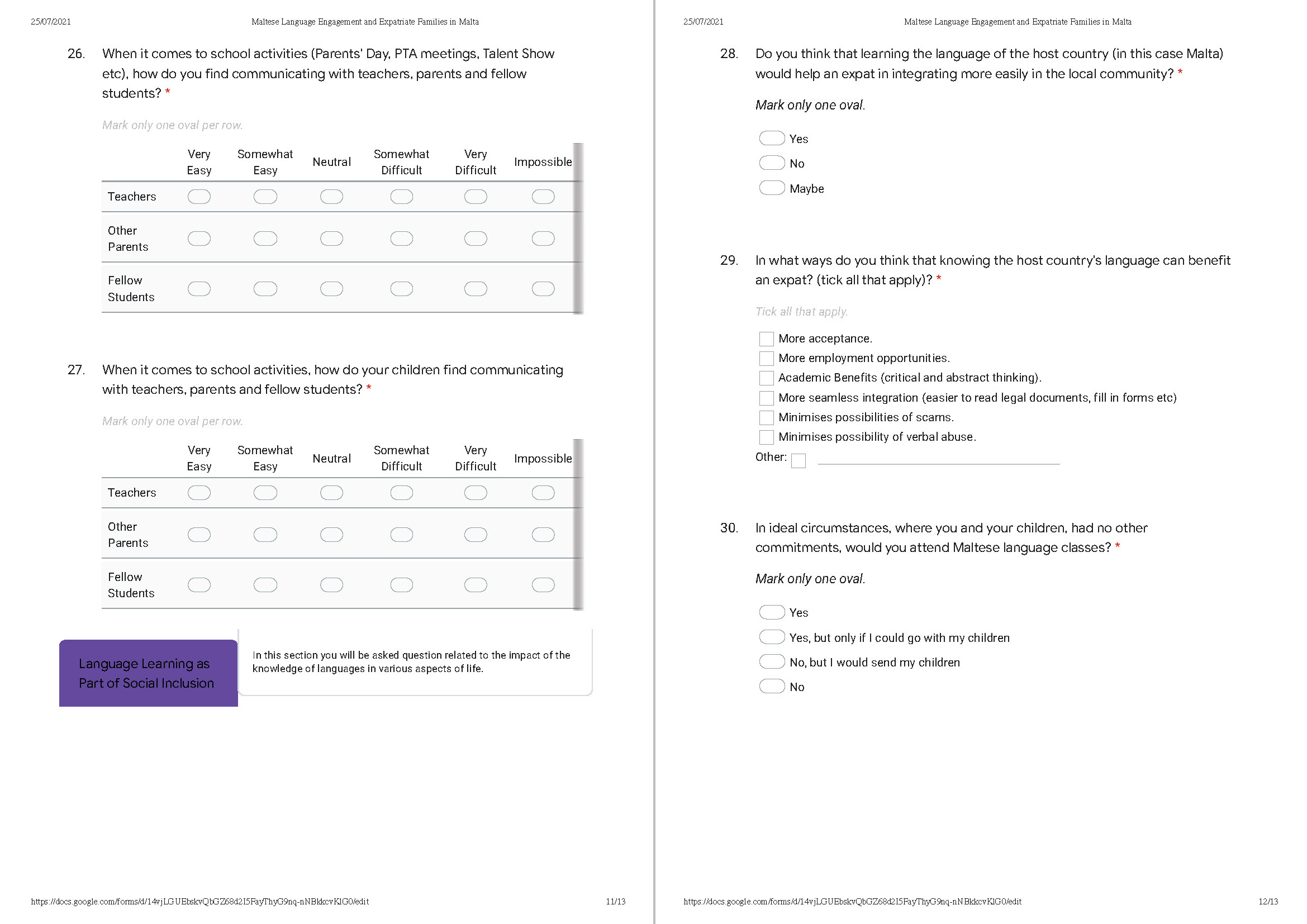

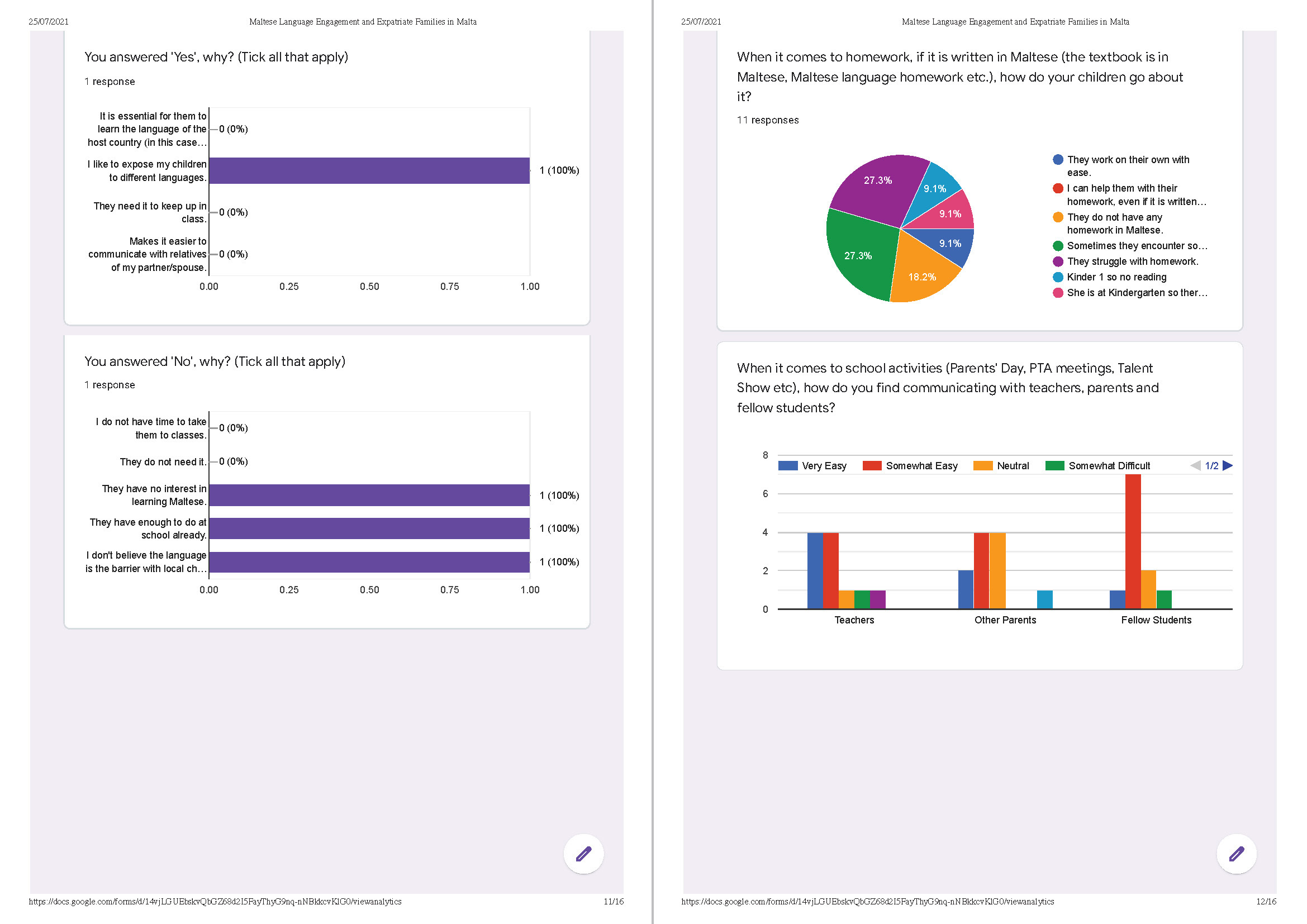

Going About School Activities

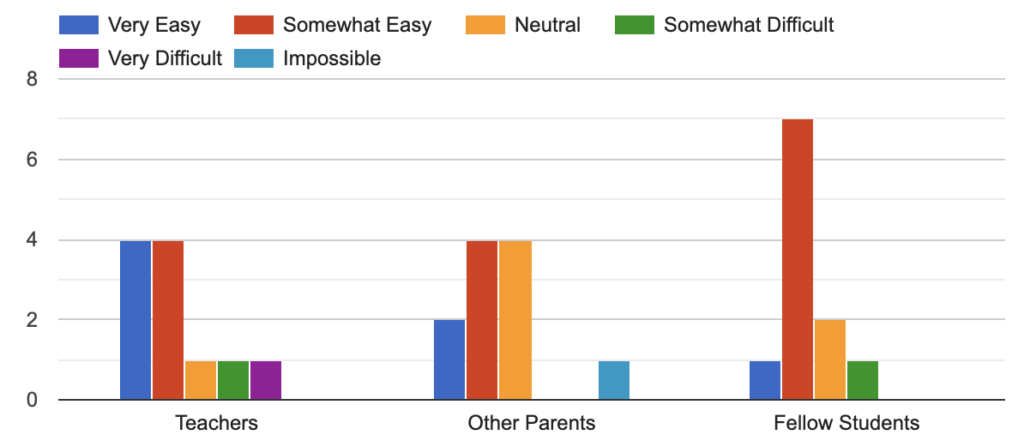

The respondents were asked how they and their children handle communication in school activities such as PTA meetings, Parents’ Day, and the School Talent Show. In both instances they were ask how they communicate with ‘teachers’, ‘other parents’ and ‘fellow students’. When they were asked about themselves, the results varied, even though the majority selected ‘somewhat easy’ in all three instances. In addition, some respondents did find communicating with teachers very easy – 4 respondents, and some others are ‘neutral’ when it comes to ‘other parents’ – 4 respondents.

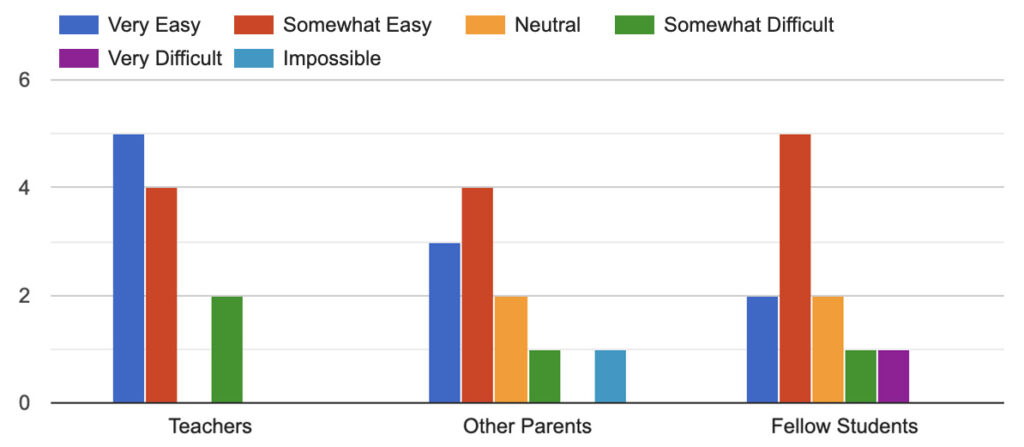

However, when it came to how the children handle communication, the results fluctuated more. In two instances, a respondent claimed that is ‘impossible’ for his child to communicate effectively with ‘other parents’ and ‘fellow students’. As for communicating with teacher, no respondent claimed that their child finds it ‘impossible’ to communicate with their teacher. The majority in fact find it ‘very easy’, and when it comes to ‘fellow students’ the majority find it ‘somewhat easy’.

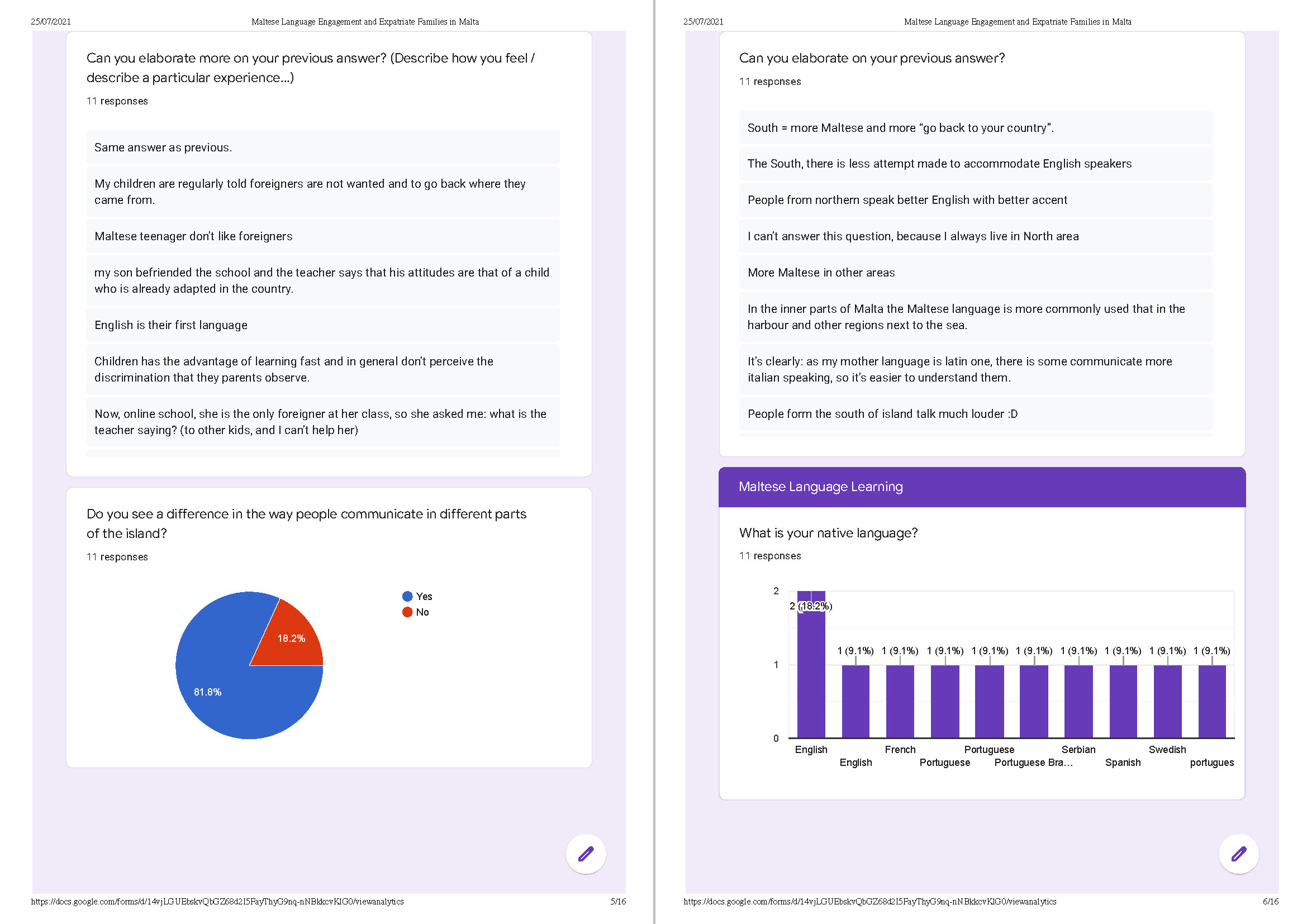

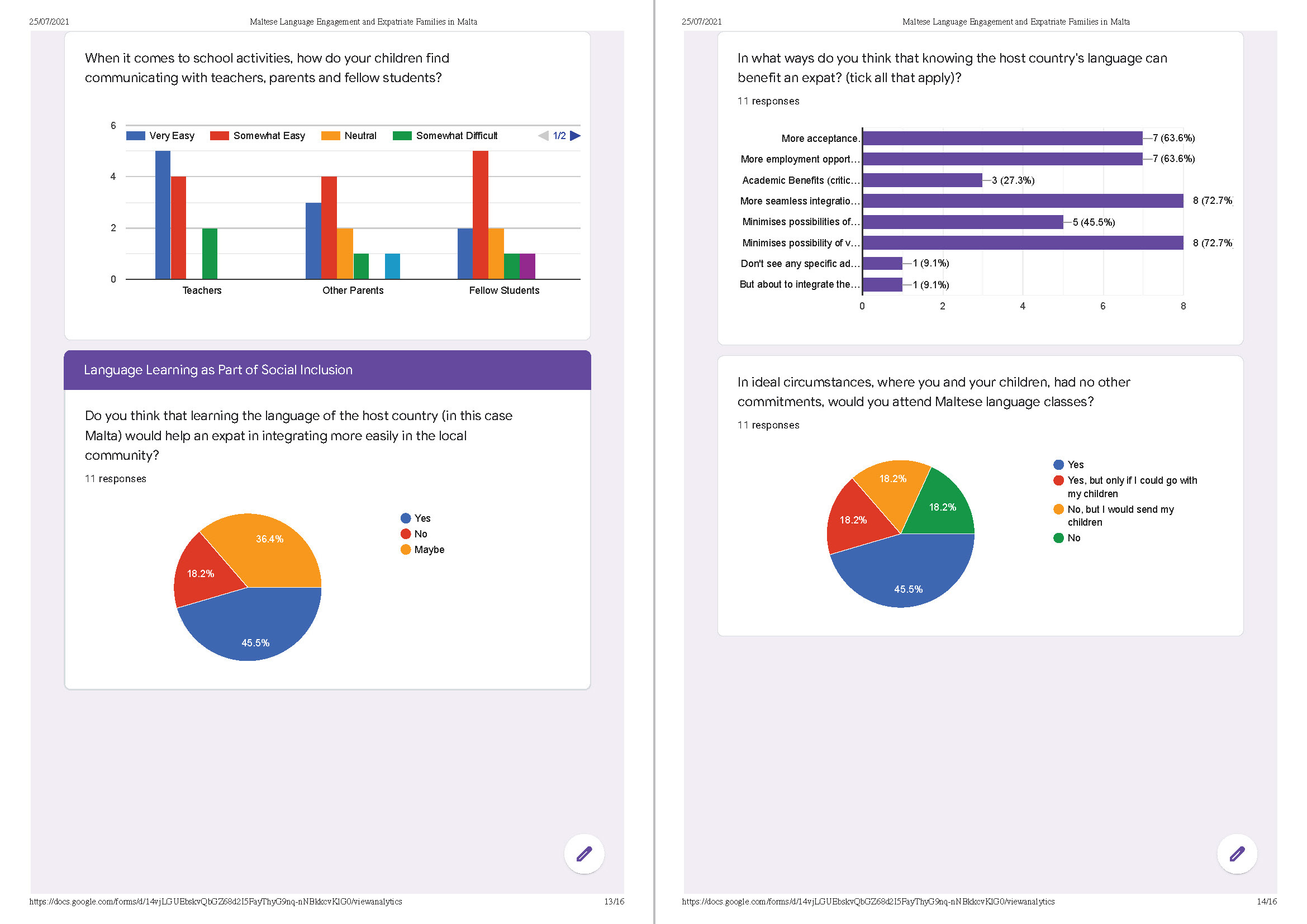

Language Learning as part of Social Inclusion

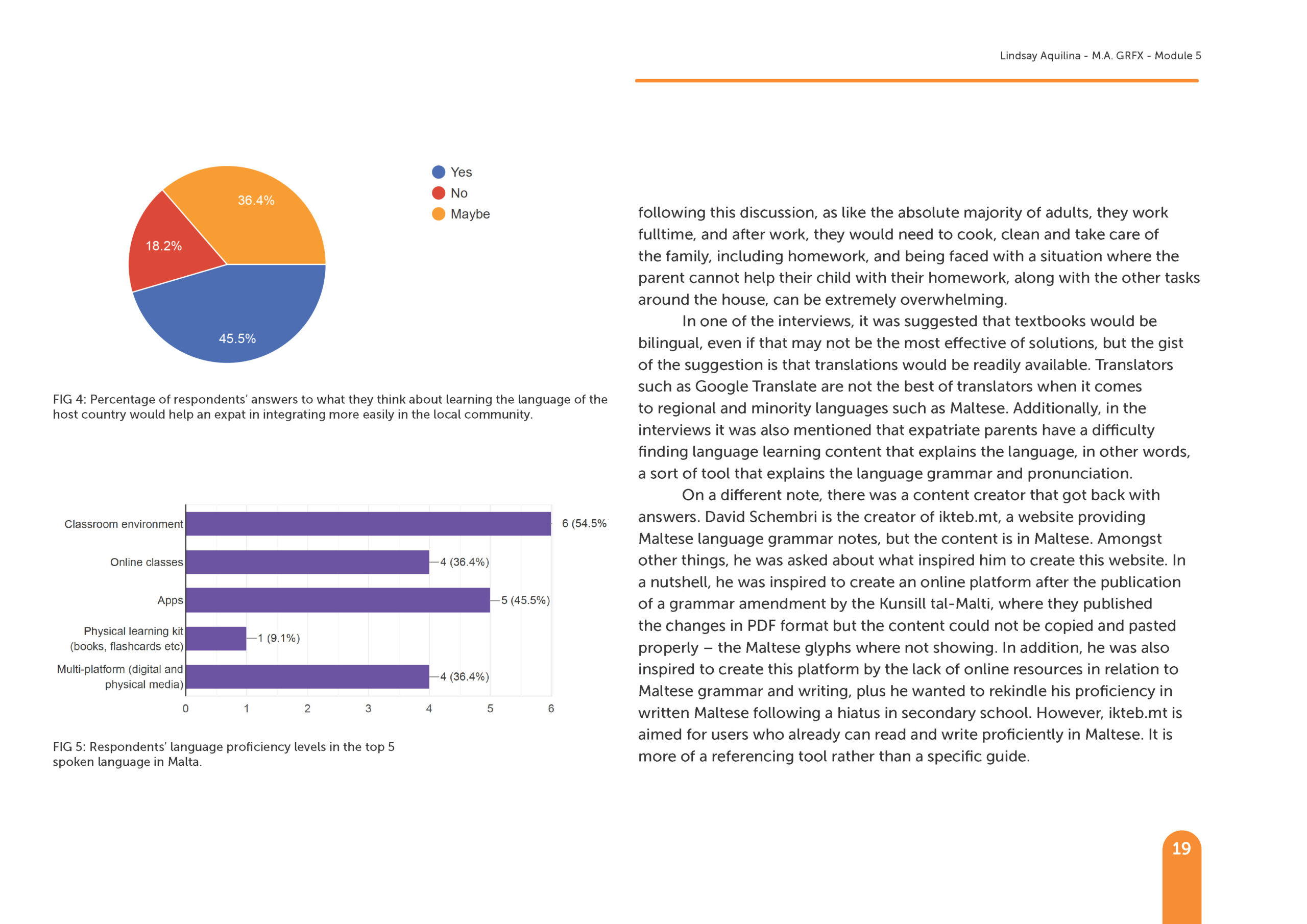

In the last section of this survey, the respondents were asked about the Maltese language in relation to social inclusion. Firstly, they were asked whether they would consider learning the language, given the ideal circumstances. Even though 45.5% of the respondents said ‘yes’, 36.4% said ‘maybe’ and the rest said ‘no’. As this may contradict the previous data regarding Maltese language learning classes, where the majority said ‘no’, it could be the case that they chose not to do so simply because of other life commitments.

The ones that chose ‘yes’, they understand that through language, one is more likely to be accepted in a community, in addition to increased employability and academic benefits. An interesting reason given was in relation to verbal abuse.

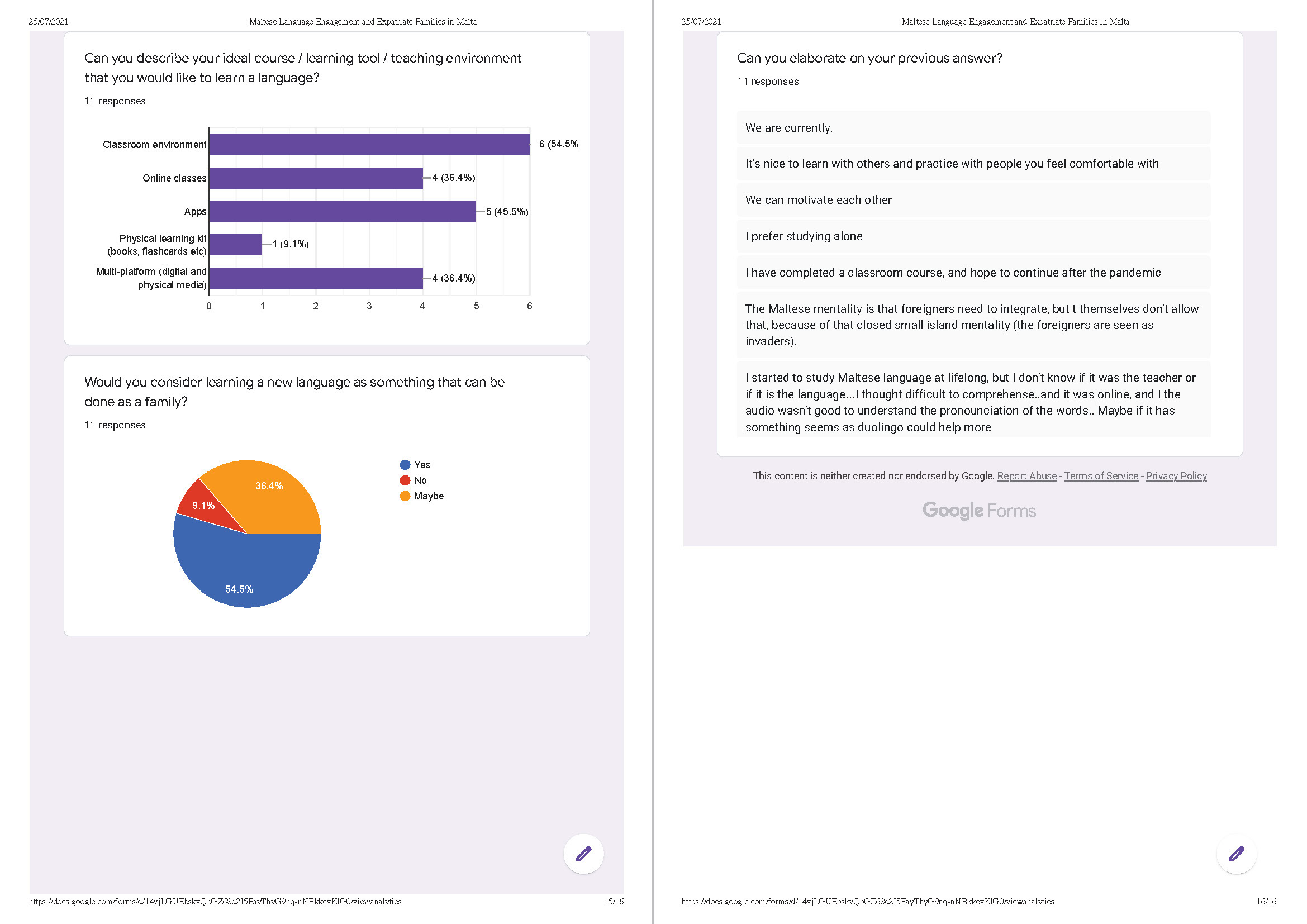

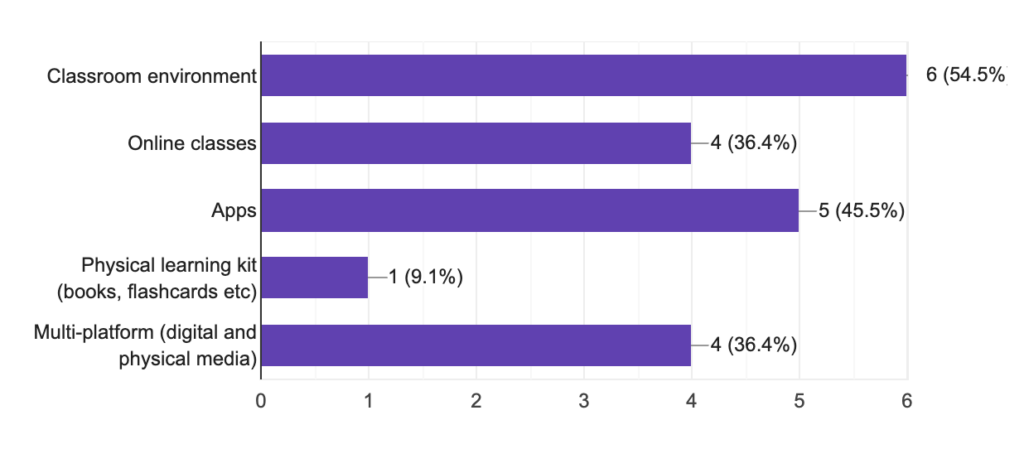

In conjunction to the above, the respondents were also asked about classes that included their children and the preferred learning environment. 45.5% said ‘yes’ they would, whilst 2 respondents said that they would go, but only if they can bring in their children with them and the other said ‘no’ but would consider classes for her child respectively. When it came to learning environments, as expected, the classroom environment was the most popular choice.

Lastly, the respondents were asked what they think of language learning being a family activity. Out of the 11 respondents, 54.5% said ‘yes’ and 36.4% said ‘maybe’. When asked to elaborate on their answers, the answers varied greatly. Some were very keen and all for getting into language learning as a family unit, and that if there is a unified interest and knowledge sharing, it can be a very effective way of learning. However, the ones that were against it, some argued that Malta is a bilingual country, and in some instances, the Maltese do not really allow foreigners to integrate.

For a complete breakdown of the data, you can follow the link here.

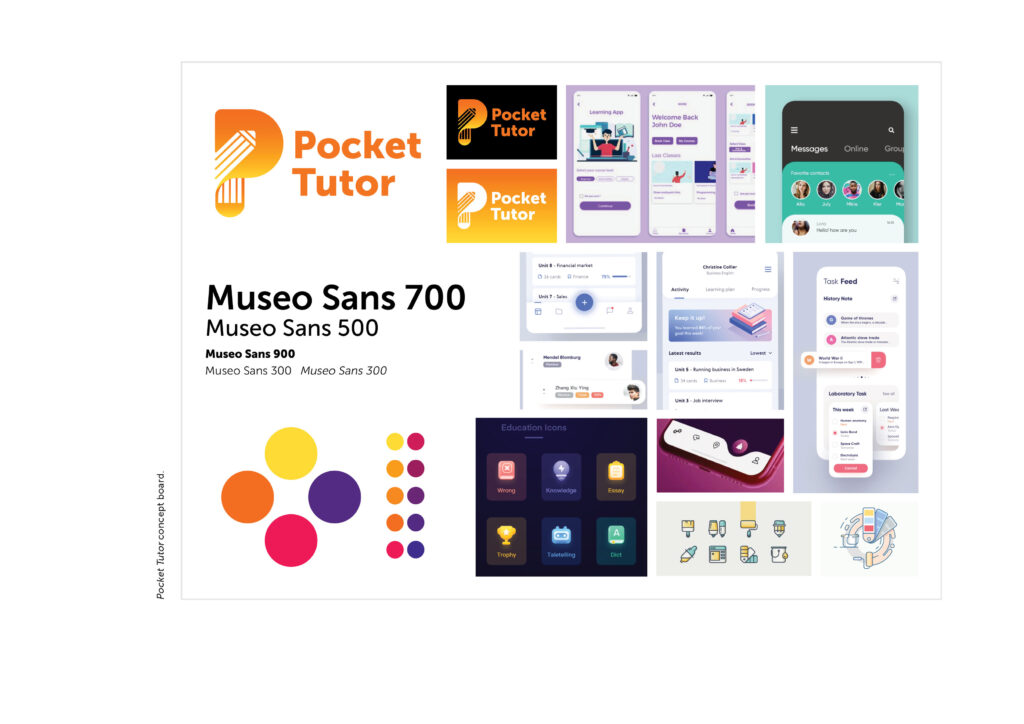

The Brand

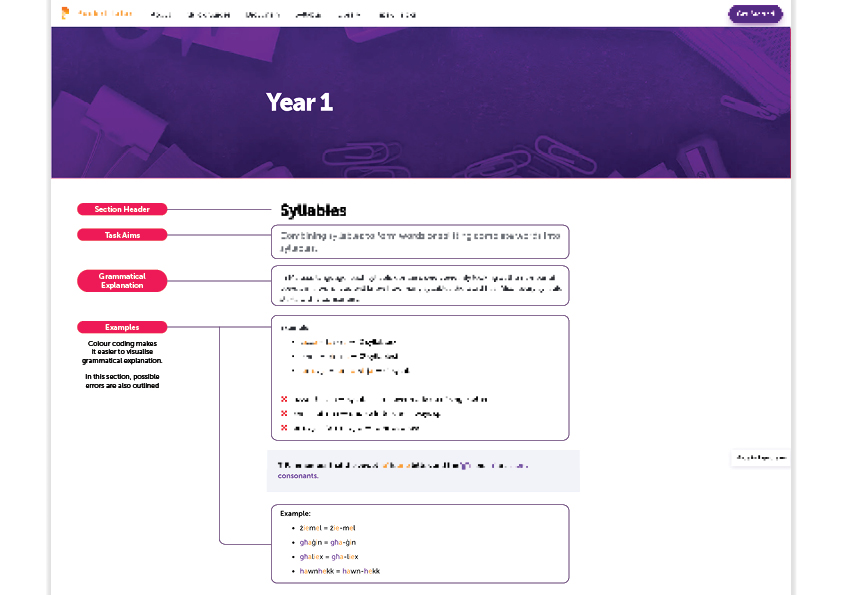

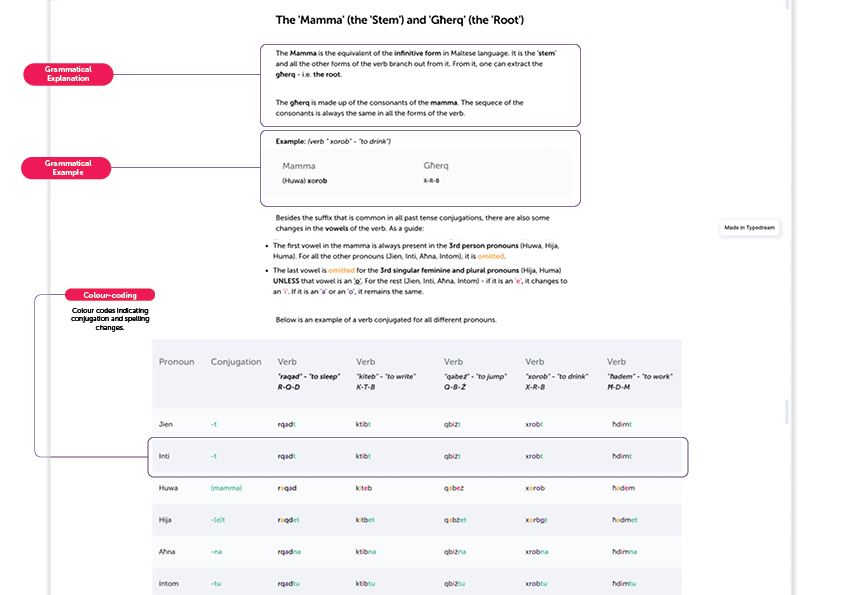

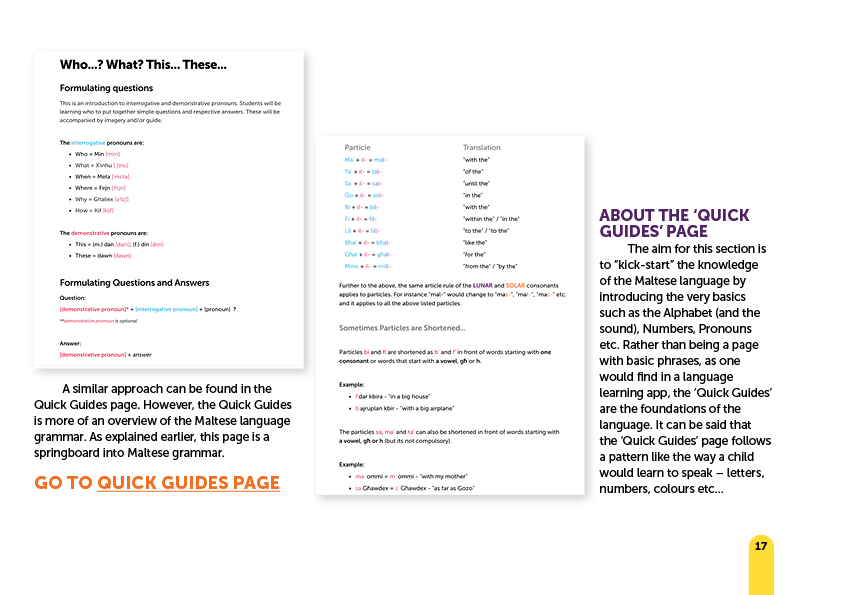

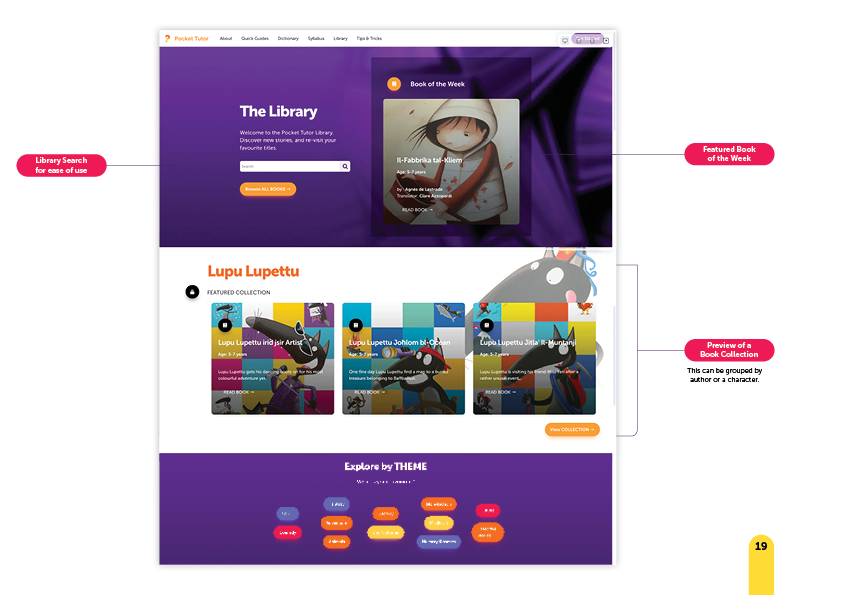

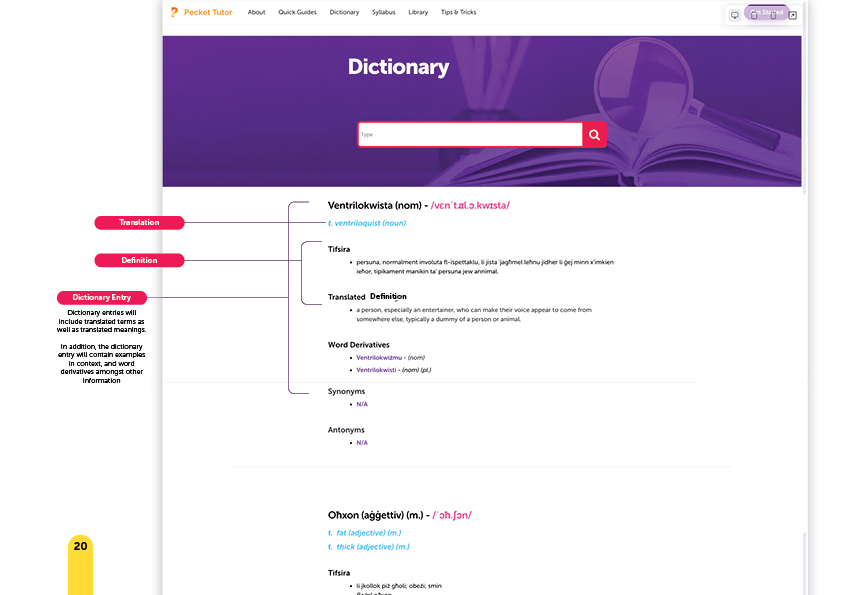

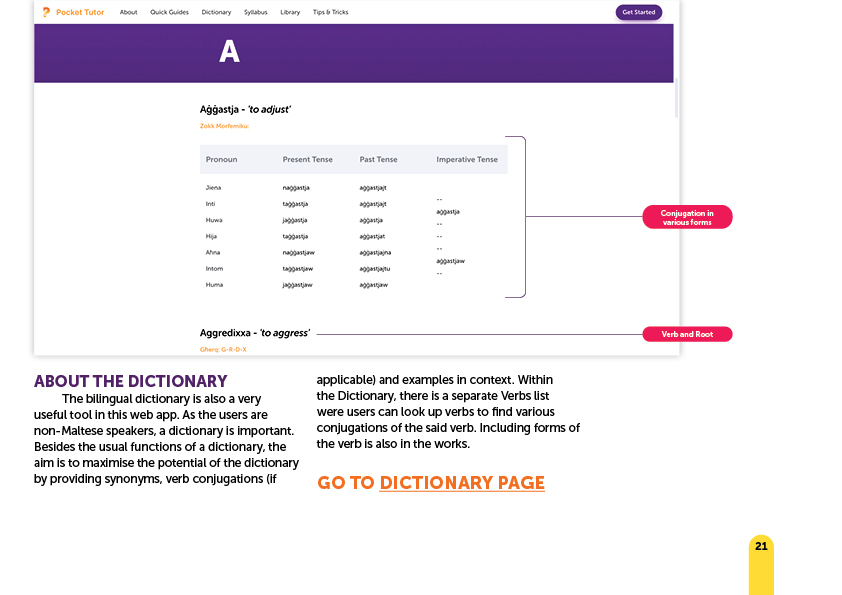

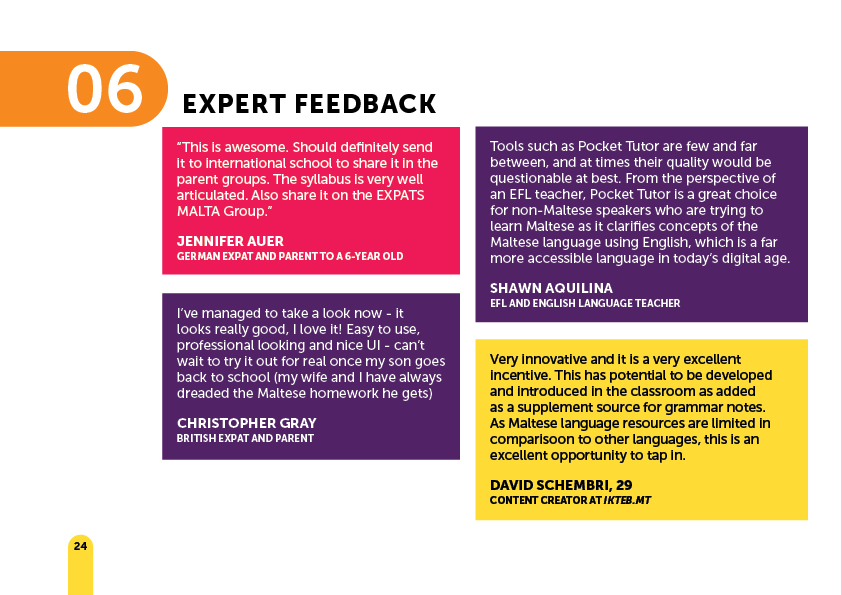

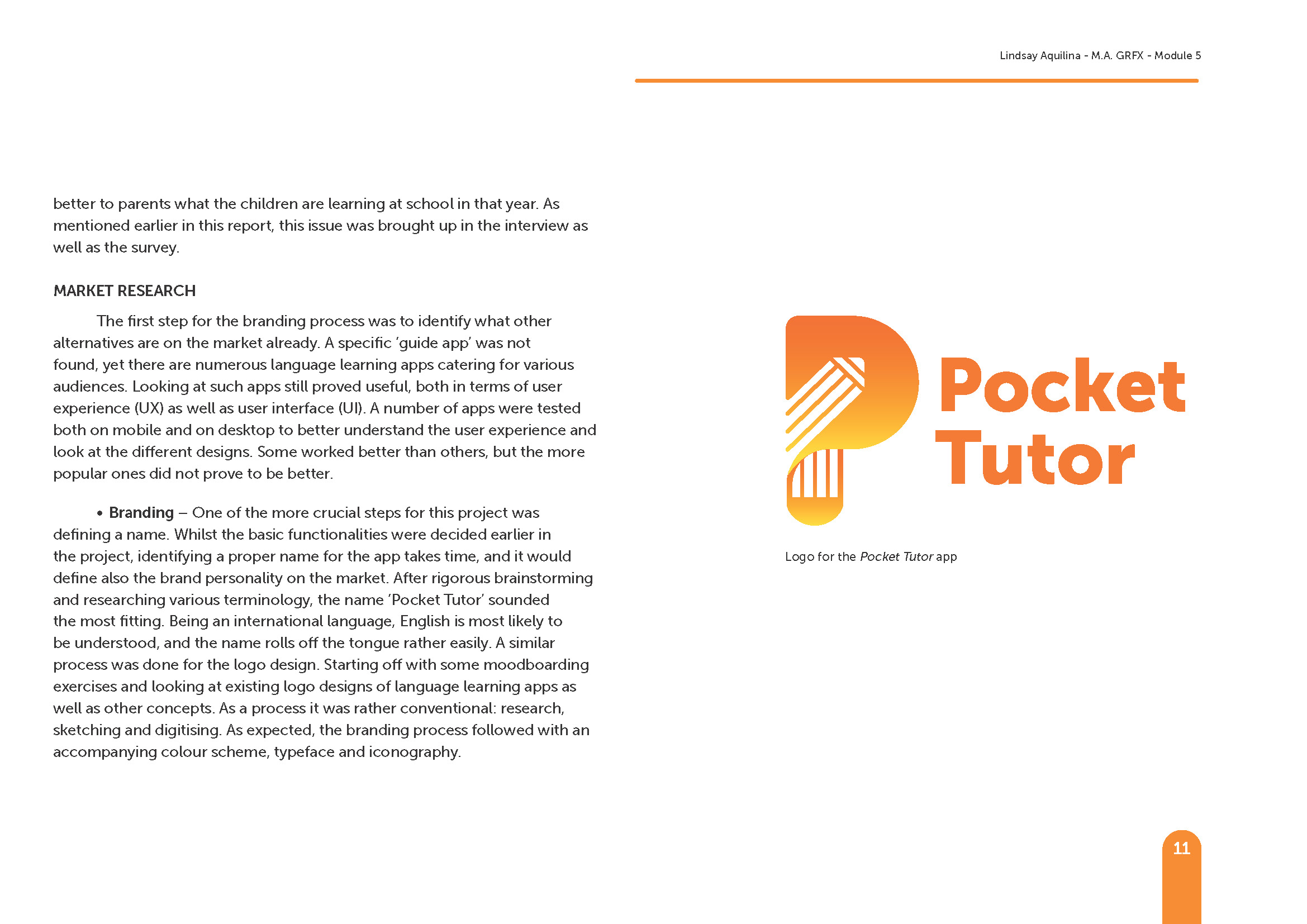

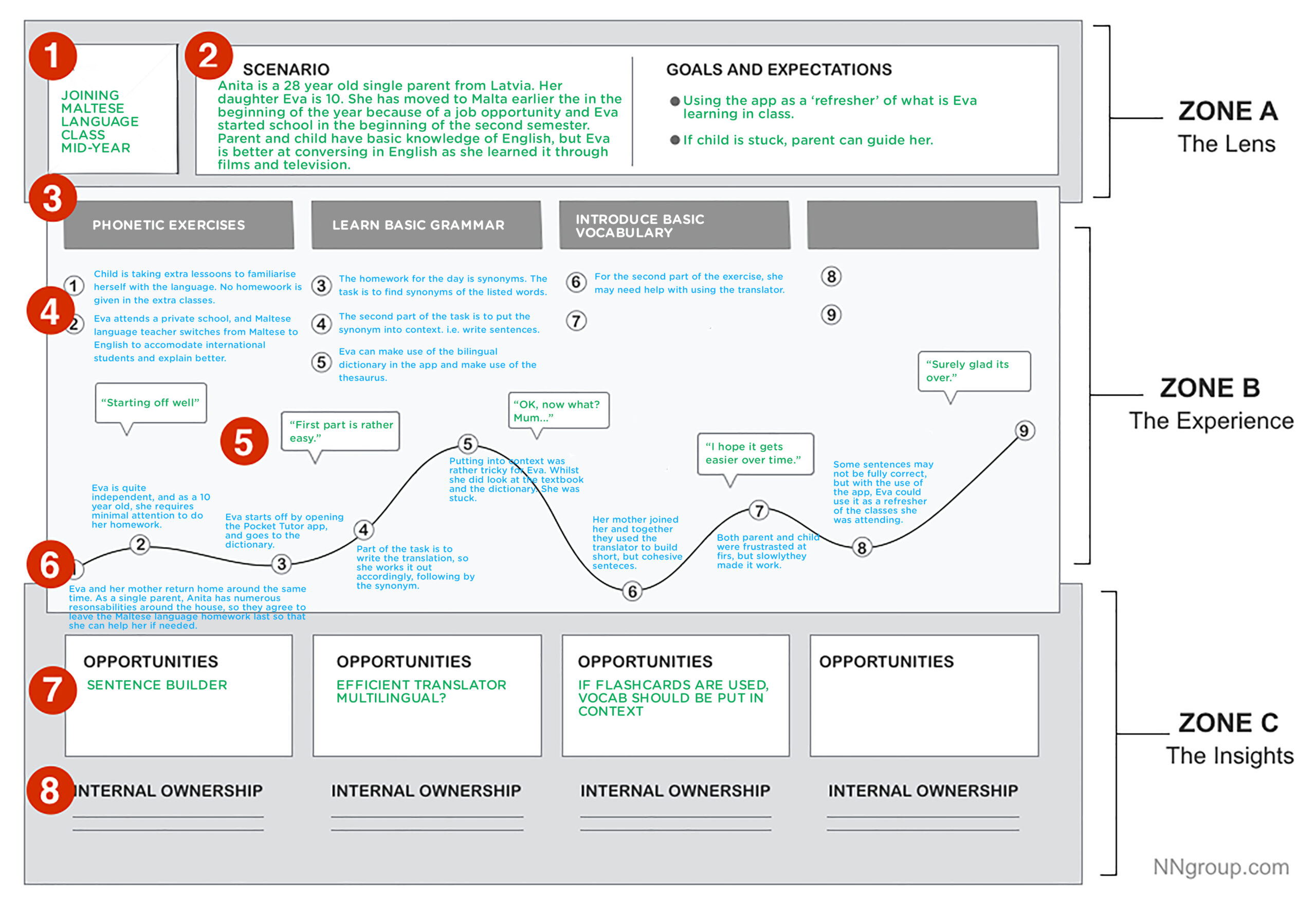

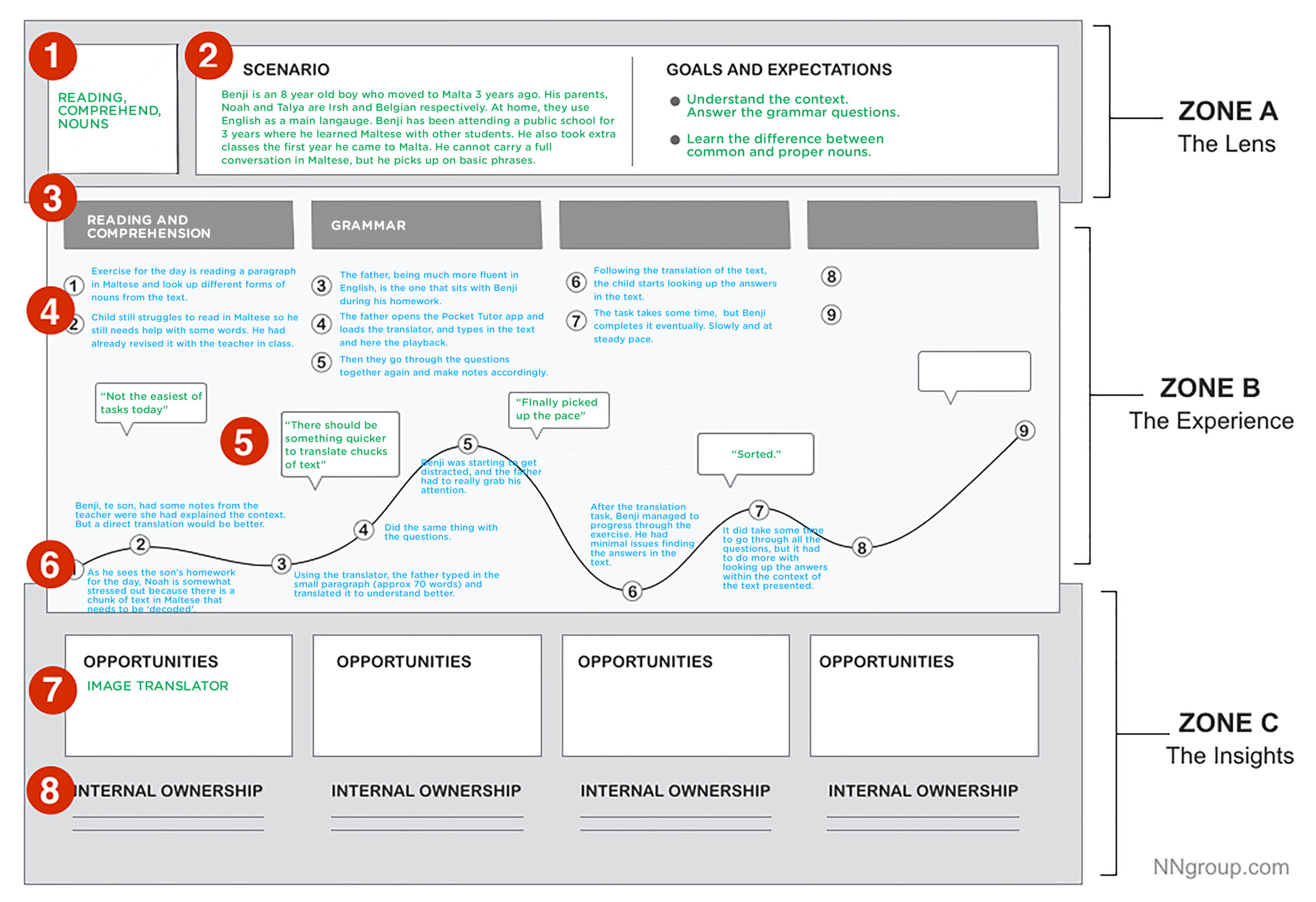

Pocket Tutor is a platform providing grammar notes for the Maltese language, explained in English to cater for non-Maltese speaking parents to help the children with their Maltese language homework. It is also a learning resources to prepare the children in advance when starting out in a Maltese school.

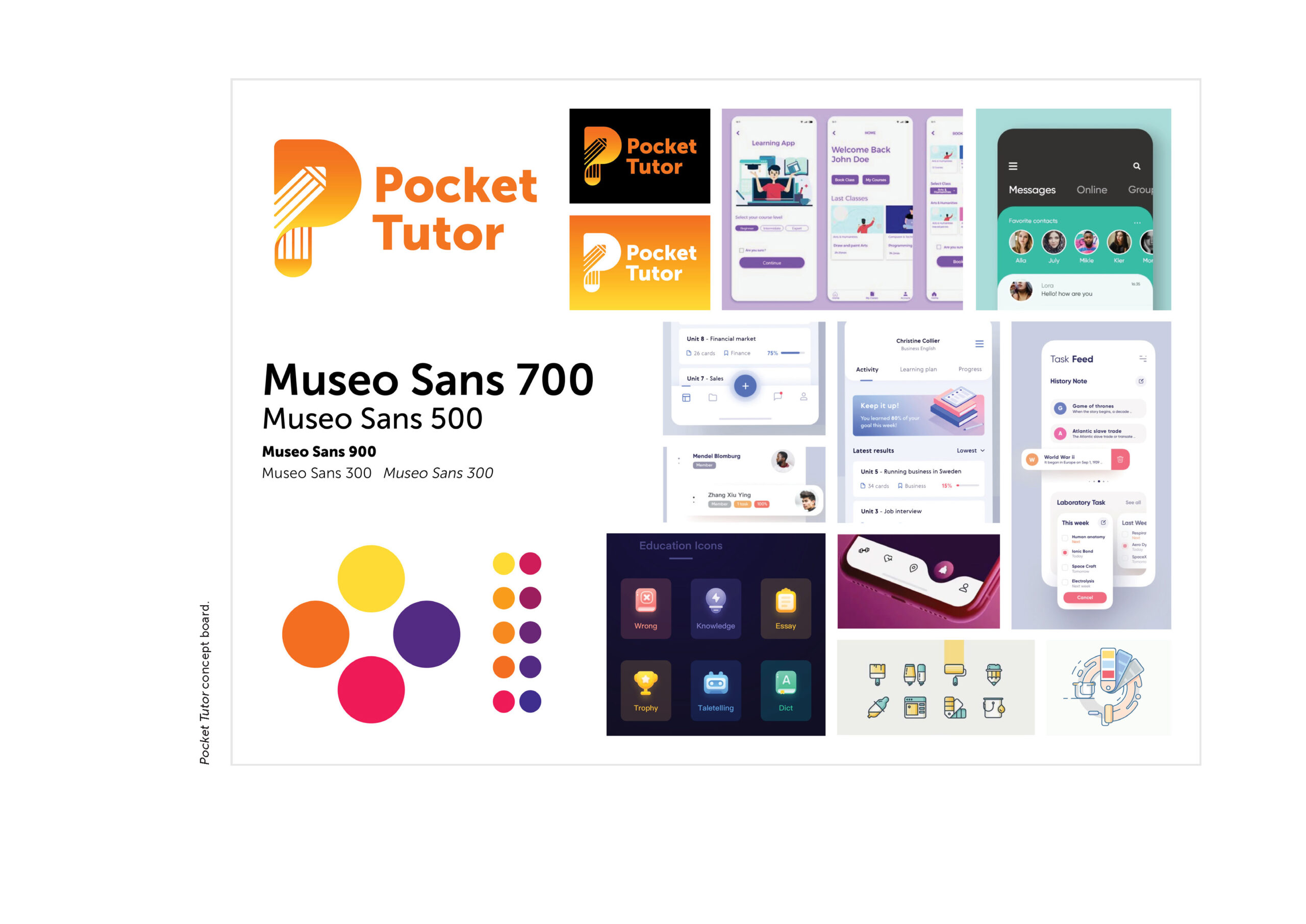

I chose this logo design and colour scheme as it works in various colours and can be easily produced on various media, both print and digital. Also, I settled on the yellow and orange as it conveys a friendly and welcoming impression. Yellow is indeed known to be ‘the colour of happiness’. Below is the final concept board for this brand. Such an exercise helps me in visualising better the brand personality, and it is a good way of referring back to it along the project to keep the work in check. In addition to the logo and typeface of choice, I included some UI and iconography styles for inspiration.